The Role of the Churches

The stated purpose of the Indian Residential Schools was to make the Indigenous Peoples of Canada embrace Western values and Christianity (those two sets of beliefs were almost inseparable at the time). In the eyes of many state officials, the agent that could and should bring about such rapid change was the Christian church. Missionaries of all denominations embraced the cause of Christianizing and civilizing the Indigenous Peoples in Canada long before the Davin Report of 1879. Indeed, in the 1880s there were already four church-run boarding schools in operation. 1 Frustration with day schools and other forms of missionary work led all the Christian denominations to support the model of boarding or residential schools. In the decades to come, the government turned over operation of most of the residential schools to the Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches. 2 Most people of European descent at the time shared the view that Christianity and civilization supported each other (if they were not actually synonymous). As early as 1852, Rev. Samuel Rose, the principal of Mt. Elgin residential school at the time, explained:

[The education of these] youths has been regarded by me as the work of no ordinary character; an education solemnly important in his connection to the future, with the unborn periods of the time. . . . These youths are to form the class whose histories is to be a most important epoch in the history of the nations to which they belong. . . . This class is to spring a generation, who will either perpetuate the manners and customs of their ancestors, or being intellectually, morally and religiously elevated, take their stand among the improved, intelligent nations of the earth, their part in the great drama of the world’s doing; or off want of necessary qualifications, to take their place and perform their part, be despised and pushed off the stage of action and ceased to be! 3

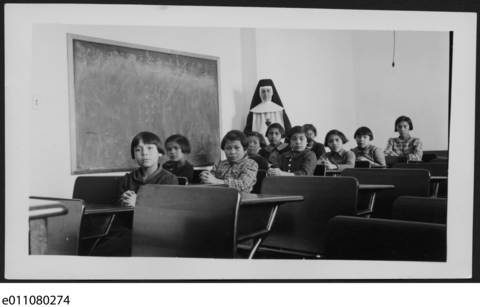

Although government funded, the residential schools were operated by churches, with clergymen and women serving in most teaching and administrative roles. This photo was taken at Cross Lake Indian Residential School in Manitoba in 1940.

A memorandum of the Convention of Catholic Principals in 1924 expressed similar sentiments:

All true civilization must be based on moral law, which Christian religion alone can give. Pagan superstition could not suffice . . . to make the Indians practice the virtues of our civilization and avoid its attendant vices. Several people have desired us to countenance the dances of the Indians and to observe their festivals; but their habits, being the result of free and easy mode of life, cannot conform to the intense struggle for life which our social conditions require. 4

The clergymen and women who took on administrative and teaching roles in the schools often saw themselves as a protective force for the Indigenous people without considering the perspectives of the cultures from which their students came. A 1911 report of the Alberta Methodist Commission said this:

The Indian is the weak child in the family of our nation and for this reason presents the most earnest appeal for Christian sympathy and cooperation . . . [W]e are convinced that the only hope of successfully discharging this obligation to our Indian brethren is through the medium of the children, therefore education must be given the foremost place.” 5

A 2012 report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission explains the complicated role of the churches:

To both Protestant and Catholic missionaries, Aboriginal spiritual beliefs were little more than superstition and witchcraft. In British Columbia, William Duncan of the Church Missionary Society reported: “I cannot describe the conditions of this people better than by saying that it is just what might be expected in savage heathen life.” Missionaries led the campaign to outlaw Aboriginal sacred ceremonies such as the Potlatch on the west coast and the Sun Dance on the Prairies. In British Columbia in 1884, for example, Roman Catholic missionaries argued for banning the Potlatch, saying that participation in the ceremony left many families so impoverished they had to withdraw their children from school to accompany them in the winter to help them search for food.

While, on one front, missionaries were engaged in a war on Aboriginal culture, on another, they often served as advocates for protecting and advancing Aboriginal interests in their dealings with government and settlers. Many learned Aboriginal languages, and conducted religious ceremonies at the schools in those languages. These efforts were not unrewarded: the 1899 census identified 70,000 of 100,000 Indian people in Canada as Christians. 6

- 1Other origins can be traced to pre-Confederation educational experiments in Europe and the array of industrial and missionary schools in the US and Canada. See John S. Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1999), 13–14.

- day schoolsday schools: Alongside residential schools and industrial schools, day schools were part of the residential school system for Indigenous children in Canada. Often located on the reserves, these schools served about two-thirds of Indigenous students throughout the history of the system. They were operated by both municipal authorities and the churches, and they attempted to reach the same goals as the Indian Residential Schools: Christianization and assimilation. Many of the troubles and abuses found in the residential schools were also found in the day schools.

- 2Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children, 15. The two largest religious organizations behind the residential schools were the Roman Catholic Oblates Order of Mary Immaculate and the Church Missionary Society of the Anglican Church (the Church of England). They became the main organizations behind the system, with the Roman Catholic Church running as many as 60% of the schools, the Anglican Church 25%, and the United Church of Canada (created after 1925 as a merger of several Protestant denominations, including the Presbyterians, Methodists, and smaller denominations) running the remainder. The Jesuits, despite their intense missionary work in Canada (early on) and around the world, operated only two residential schools after Confederation. The Methodist and Presbyterian Churches in Britain and the US operated a few schools, as well.

- 3Rev. Rose Report, 1852, in Elizabeth Graham, ed., The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools (Ontario: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 230. Emphasis added.

- 4Memorandum of the Convention of the Catholic Principals of Indian Residential Schools, Lebert, Saskatchewan, August 28–29, 1924.

- 5T. Ferrier, “Report for the Alberta Methodist Commission,” 1911, quoted in John Milloy, A National Crime, 28.

- Truth and Reconciliation CommissionTruth and Reconciliation Commission: Truth and reconciliation commissions have become commonplace since the 1970s. They reflect a global trend of paying greater attention to mass violations of human rights. Most of a commission’s work is focused on crimes carried out by a government against its own citizens. Since the 1970s, there have been at least 40 truth and reconciliation commissions established worldwide, and some are still active today. Truth commissions involve a multifaceted process designed to help victims overcome historical injustice and trauma and reconcile with those who harmed them. Part of what experts call transitional justice, a truth and reconciliation commis- sions typically includes the elements of truth-seeking, justice, and reconciliation. Established under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Canada’s commission began collecting survivor testimonies and related historical information in 2010. In an effort to make this information public, the commission’s archive was opened in 2014. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its final report, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future, on June 3, 2015.

- 6Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children, 15.

Although government funded, the residential schools were operated by churches, with clergymen and women serving in most teaching and administrative roles. This photo was taken at Cross Lake Indian Residential School in Manitoba in 1940.

Connection Questions

- How did Rev. Samuel Rose justify the missions and policies of the residential schools? What purpose did he believe the schools served?

- What language is used in the different passages from religious leaders to describe Indigenous Peoples and their culture? What language do these religious leaders use to describe their own mission? What might we learn from the contrasts between their motivations and their rationalization for the policy? What might the contrasts reveal about their biases?

- What, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, was the role of the churches in colonial Canada? Is it possible to reconcile the two main roles identified by the report (an assault on and protection of Indigenous culture)? If yes, how?

- The Introduction to Chapter 2 described Helen Fein’s definition of a universe of obligation—the circle of individuals and groups “toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for [amends].” 1 How might the religious leaders in this reading have described their obligation to the Aboriginal Peoples? How did they propose to express that obligation? How did those ideas conflict with Indigenous beliefs, expectations, and rights? Based on what you’ve read so far, what might Fein say about the way some of the religious leaders quoted in the reading defined their universe of obligation?

- 1Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide (New York: Free Press, 1979), 4.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "The Role of the Churches," last updated October 16, 2019.