World War: Choices and Consequences

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

Grade

6–12- The Holocaust

Overview

About this Chapter

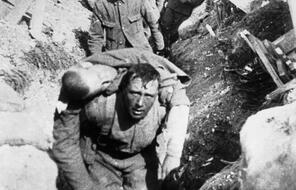

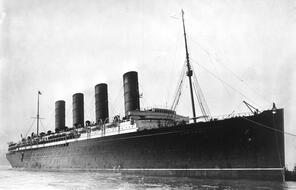

The ways societies define “we” and “they” can help to precipitate war. In turn, the violence and chaos of war can sharpen the differences people perceive between their nation and others, as well as between different groups within their own nation. This chapter focuses on how World War I shaped and was shaped by ideas of “we” and “they,” and it highlights aspects of the war that influenced the history of Nazi Germany in the following decades.

Inside this Chapter

Analysis & Reflection

Enhance your students’ understanding of our readings on World War I with these follow-up questions and prompts.

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand