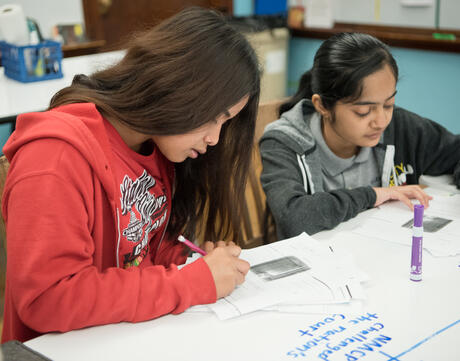

KEVIN TORO: One thing about using journals in class that I find really useful is, as teenagers, they are so willing to sort of write their thoughts down, organize what they're thinking. And often when we have them speak in class, that there's a little bit of disconnect that happens as they're trying to think and put norms on it and everything that goes along. And with writing, at least from what I've seen and experienced, they seem less limited. They seem almost more willing to talk about harder topics. They get right to it. And it's been something that's really helped me in terms of reflection.

Journals as a tool to get them ready. They are using their sort of own thoughts. They know that it's going to be collected, so it is a bit of work, and there's a bit of tension there. They know that there's going to be outcomes that are going to be assessed. They also feel personal to them in a lot of ways. And they use it constantly throughout class.

For today, what is freedom and what does it mean to be free? You have, let's say five minutes. And then we'll talk a little bit about that freedom. We have this question, what is freedom? And then we have another question. What does it mean to be free? We're talking about a time, remember, where we have a lot of people who have acquired new given citizenship. They are emancipated. They are now citizens in this country. They have full rights.

We know necessarily, from what we've already looked at, that that's not the full truth, but we're going to analyze that to come to our own sort of conclusions about it. If I could take any volunteers for what is freedom and what does it mean to be free. Remember, you could place it in the context. You can also place it out of context. Doralee.

DORALEE: I think freedom is the collection of basic rights and the constitutional rights. It's the ability to express yourself willingly and throughout the government and have a voice in it. And I said that it means everything to a person, because it allows them to be an individual and pursue happiness and live the way they want to live.

KEVIN TORO: Wonderful, yeah. What a great definition of freedom. Gus, I saw you had your hand up.

GUS: Freedom is like the right not to be owned by anyone.

KEVIN TORO: Yeah. Well, especially in the time period we're talking about, that seems so pertinent as an idea. In your own words, describe the freedom given to the former slaves. How does this compare with the definition that you already put from your journal earlier today? What I would like is to take a little bit of time for these. And then hopefully, share. But I'll give you, let's say two, three minutes, and then we'll check in, OK?

If I could ask you to do something last two minutes of class, I just want to get a few answers. How do these compare? And in your own words, what is this freedom? Diego, start us off.

Diego: Education. And I felt like with all the things that I read during the whole session, I feel like that's what I got the most from the readings. To them, like receiving the proper education was most important and like I hadn't thought about that when I wrote my definition. All I thought about was just like being able to go where I please and like freedom of speech and stuff like that. But to them, it was education.

KEVIN TORO: Doralee.

DORALEE: The freed slaves had to work like twice as hard just to like gain their freedom. And I think like nowadays, we take things for granted, like education, the right to just living free or just anything that we want to do. And we have to remember like these people actually had to fight for their freedom. It's not like something that was natural to them. So I think that a lot of people forget where we came from.

KEVIN TORO: Yeah, and the struggle it is, what freedom is in my opinion, is a struggle. Amelia, finish us off.

AMELIA: Um, kind of related to Doralee's, I said like the freedom they're given was also more responsibilities in the world, like their whole community and like society, rather than just in their own personal lives. And like they definitely act upon their freedom a lot more and like don't take it for granted as much.

KEVIN TORO: Absolutely. Opportunities as well. All right, everyone. Thank you so much. Today was great. I use journals in class as a way to allow the students to connect with their inner thoughts, especially in the class around racism. There's a lot of deconstructing of sort of myths and barriers that the students have to do. The journals allow them a safe space to really think, put down their thoughts.

Using it throughout the class period, beginning sort of middle and end, really also allows them a point to check in and breathe, which I really love. And so they get to not only access the information for themselves, reflect, but they just get a chance to actually some little bit of downtime. I think if all of us write journals, we know how comforting they can be.