uses lessons of history

to challenge teachers

and their students

to stand up to bigotry and hate.

We are Facing History

Facing History & Ourselves is more than our name. It is an active and continuous process that calls on each of us to connect the choices of the past to those we face today. To build a more just and equitable future, we must face our history in all its complexity, Are you ready to face history with us?

Learn how you can experience Facing History

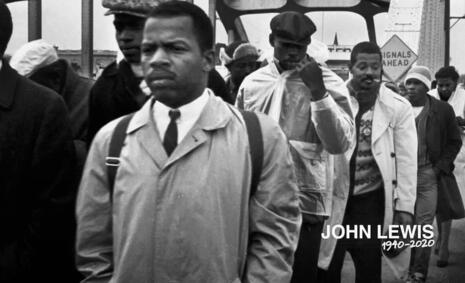

John Lewis

Civil Rights Leader and Congressman Get Inspired by John Lewis’ Legacy

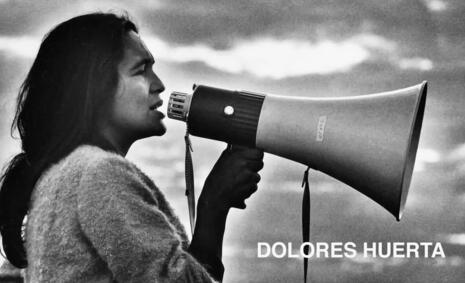

Dolores Huerta

Activist and Upstander Learn How to Stand Up from Dolores Huerta

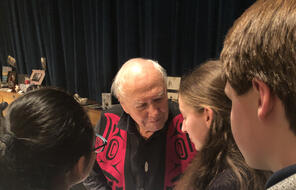

Elie Wiesel

Holocaust Survivor and Author Teach “Night”, Elie Wiesel’s story of survival

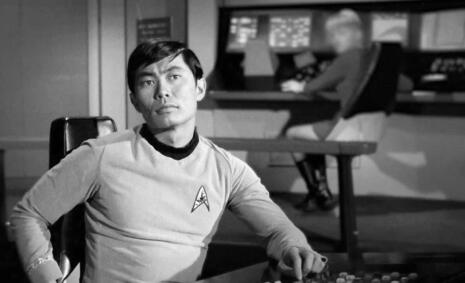

George Takei

Japanese American Incarceration Survivor and Entertainer Examine Difficult History with George Takei

Choices make history.

Teach Facing History

Not in the United States?

Find resources for Canada and the United Kingdom

Learn more about our other International Partners

Sign Up

And hopefully, they will always remember what happened to us and make sure that it won't happen again.

Sonia Weitz, Holocaust survivor and poet

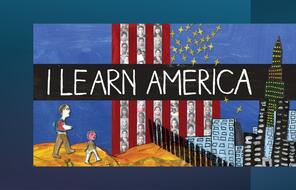

Access the digital version of this book.

Don't miss out!

- download classroom materials

- view on-demand professional learning

- and more...

Our Impact

-

Facing History students are 94% more likely than their peers to report that their class motivated them to learn.

-

92% of Facing History teachers agree that Facing History helps their students stand up for what they believe even when others disagree.

-

91% of elective teachers agree or strongly agree that their Facing History course promoted their students’ abilities to ground reading, writing, and speaking in evidence from text.