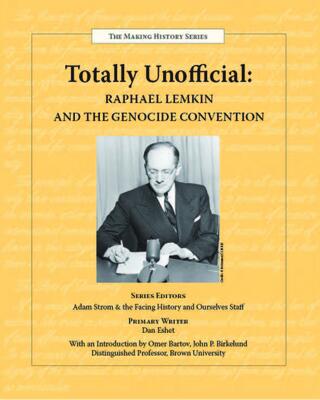

Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Human & Civil Rights

- The Holocaust

Conventional Revolution: Raphael Lemkin and the Crime Without a Name

At the end of World War II, leaders and activists set out to build new institutions, like the United Nations, that could foster international cooperation and safeguard peace. They also worked to establish new international standards, laws, and treaties in the hope of preventing future crimes like those perpetrated by Nazi Germany. But before World War II ended, the Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin had already been working for decades to make the world recognize mass murder as an international crime. The scale of atrocities in World War II gave Lemkin’s mission a new urgency.

Raphael Lemkin: Watcher of the Sky (Introduction)

Lemkin was a university student in the 1920s when he learned about the coordinated massacres of Armenians during World War I (see reading, Genocide under the Cover of War in Chapter 3). He was horrified to find out that no international laws existed to prosecute the Ottoman leaders who had perpetrated these crimes. Lemkin asked, “Why was killing a million people a less serious crime than killing a single individual?” 1 Forty-nine members of Lemkin’s own family were later murdered in the Holocaust. Lemkin himself had fled to the United States, where he struggled to draw attention to what Nazi Germany was doing to European Jews—massacres that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called “a crime without a name.” 2 In 1944, Lemkin made up a new word to describe these crimes: genocide. Lemkin defined genocide as “the destruction of a nation or an ethnic group.” He built the word, he said, “from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homicide, infanticide, etc.” He wrote, “Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.” 3 This was an important element of the definition of genocide: people were killed or excluded not because of anything they did or said or thought but simply because they were members of a particular group. For Lemkin, genocide was an international crime—a threat to international peace and to humanity’s shared beliefs.

- 1Raphael Lemkin, “Genocide,” American Scholar 15, no. 2 (1946): 228.

- 2Winston Churchill, Never Give In! The Best of Winston Churchill’s Speeches (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 300.

- 3Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress, 2nd ed. (Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange, 2008), 79.

Raphael Lemkin: Watcher of the Sky (Genocide Convention)

When World War II ended, Lemkin returned to Europe and served as an advisor to Justice Robert H. Jackson, the lead prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials (see reading, The First Trial at Nuremberg in Chapter 10). Lemkin considered the Nuremberg trials only a partial success, for while they did punish some of those who were guilty of genocide against European Jews, Nazi leaders were indicted on the broader charge of “crimes against humanity” and the Jewish identity of victims was not emphasized. Genocide still was not recognized in law as a crime. Lemkin wrote, “In brief, the Allies decided a case in Nuremberg against a past Hitler—but refused to envisage future Hitlers.” 4 Therefore, after the trials, Lemkin devoted himself to persuading the newly formed United Nations to “enter into an international treaty which would formulate genocide as an international crime, providing for its prevention and punishment in time of peace and war.” 5

Lemkin successfully persuaded the UN to act. On December 9, 1948, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, often called the Genocide Convention, which classified genocide as a crime under international law and incorporated many, though not all, of Lemkin’s ideas. (It did not offer protection for political groups, for example, as he had recommended.) The convention states, in part:

Article I

The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and punish.

Article II

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Article III

The following acts shall be punishable:

(a) Genocide;

(b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

(c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

(d) Attempt to commit genocide;

(e) Complicity in genocide.

Article IV

Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals. 6

By the 1950s, a sufficient number of countries had ratified the convention, and it entered into force (although the United States did not ratify it until 1986). In 1998, a permanent International Criminal Court was established, with jurisdiction over the most important international crimes, including genocide (see reading, The International Criminal Court). Lemkin’s contribution was enormous, though he died before he could witness a conviction for the crime he was the first to name.

- 4Raphael Lemkin, Totally Unofficial: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin, ed. Donna-Lee Frieze (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 118.

- 5 Raphael Lemkin, “Genocide,” American Scholar 15, no. 2 (1946): 230.

- 6“Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” Prevent Genocide International, accessed October 3, 2005.

Explore the Unit

Go deeper in your study of the Genocide Convention and Raphael Lemkin with our online unit and resource book.

Connection Questions

- Raphael Lemkin spoke of the importance of envisaging “future Hitlers.” What did he mean? Why might it have been important to imagine “future Hitlers” even when leaders were still trying to address the crimes of the Nazis?

- Numerous words that described mass killings were available to Lemkin, including “crimes against humanity,” “slaughter,” “race murder,” and others. He rejected all of them in favor of a word he made up himself. Does the word genocide convey something the other terms do not?

- When a people is destroyed, what is lost in addition to their lives? How does the Genocide Convention address these losses?

- Lemkin believed that new words must be created when new ideas or events “strike at our consciousness.” How can coining new words help us understand old issues? What is the role of language in dealing with social problems? How do innovations in language educate those who use the language?

- Despite the existence of the Genocide Convention, the crime of genocide has continued to be perpetrated. Since the convention was entered into force in 1951, genocides have occurred in Cambodia, in Rwanda, in Bosnia, in Darfur, and in other places around the world. Each genocide is unique, but does the persistence of genocide suggest anything generally about the limitations of international law in preventing this crime? What other tools could be used to prevent genocide? What should happen when such crimes are not successfully prevented?

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention," last updated August 2, 2016.