After Charlottesville: Public Memory and the Contested Meaning of Monuments

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

Grade

6–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Democracy & Civic Engagement

Overview

About This Lesson

Events in August 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, where white supremacists protested the removal of a Confederate monument led to violence and the death of a counter-protester, raised important issues about history, public memory, and the symbolism of public space.

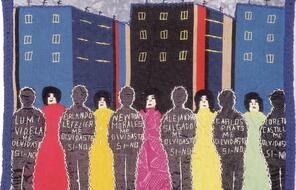

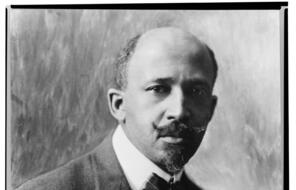

This lesson is designed to help students understand the role that memorials and monuments play in expressing a society’s values and shaping its memory of the past. The lesson invites students to explore how public monuments and memorials serve as a selective lens on the past that, in turn, powerfully shapes our understanding of the present. It also explores how new public symbols might be created to tell a countervailing narrative that seeks to change or correct the previous, dominant understanding of history.

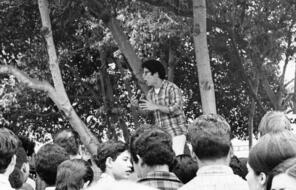

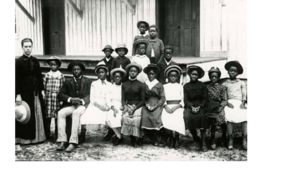

In Memphis, Tennessee, high school students and activists undertook such a project when they began to reckon with the forgotten history of lynching in their community. In this lesson, students will connect these efforts to the idea of participatory democracy, analyzing how the creation of new historical symbols can be understood as an effort to transform communities and shape collective memory. In the final activity, students will become public historians themselves. They will design their own memorial to represent a historical idea, event, or person they deem worthy of commemoration.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Additional Resources

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand