The final months of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and the immediate aftermath of his assassination marked an intensification of the nonviolent struggle on two fronts: fighting poverty and ending the Vietnam War. For Dr. King, these two issues became inseparable.

By 1967, the United States was deeply entrenched in the Vietnam War. Invoking the fear of communist expansion and the threat it posed to democracy, President Lyndon B. Johnson increased the number of US troops in Vietnam. In response, some civil rights leaders charged that President Johnson’s domestic “war on poverty” was falling victim to US war efforts abroad. Dr. King struggled with an internal dilemma about finding a proper way to publicly denounce America’s involvement in Vietnam. In a speech delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York, King told the gathered clergy that it was “time to break the silence” on Vietnam. Drawing connections between the resources spent on the war and the rampant poverty in America, Dr. King warned that the objectives of the movement were undermined by the use of force abroad. Many of Dr. King’s allies criticized his stance; they argued that it would split the movement and weaken its support base. President Johnson, who supported civil rights, saw Dr. King’s public stance on Vietnam as a personal betrayal.

In addition to the nonviolent struggle to protest the Vietnam War, Dr. King also led efforts to end poverty. The Poor People’s Campaign was the first national economic campaign led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Building on their experiences in Chicago and other cities, the SCLC embarked on a drive designed to highlight the consequences of entrenched poverty. The organization planned a multiracial campaign which would adapt nonviolence to the struggle for economic equality in America. For Dr. King, the Poor People’s Campaign was a bridge between civil rights and economics. The campaign was to end in a massive demonstration of solidarity in Washington, D.C.

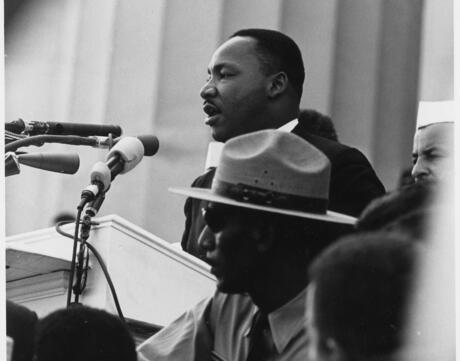

While organizing the campaign, Dr. King received a call from his friend Reverend James Lawson, the man who had organized the trainings in nonviolence in Nashville during the sit-ins. Lawson invited Dr. King to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of a black sanitation workers’ strike. Dr. King, believing the strike would highlight the link between race and poverty, accepted the invitation. On March 18, 1968, Dr. King delivered a speech to a crowd of seventeen thousand; ten days later he led protestors in a march through the city. For the first time, however, one of Dr. King’s marches descended into violence. Disturbed, he flew back home, but vowed to return and lead a nonviolent march in Memphis.

Two weeks later, Dr. King was back in Memphis. On April 3, 1968, the evening before his assassination, he delivered his passionate and prophetic “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech in Memphis at the Mason Temple Church in which he encouraged the crowd to stay unified and maintain its focus on the issue of injustice and not focus on the violence that the media highlighted in its reporting of the strike. The next day, during a meeting with Andrew Young, Rev. Jesse Jackson, and other SCLC leaders at the Lorraine Motel, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., stepped out onto his balcony. Seconds later he was hit by a sniper’s bullet; he died an hour later at a nearby hospital. The country was in shock: America had lost its most public voice of moral conscience. Disbelief quickly became fury, and on April 5, riots broke out in more than sixty cities across the US. For several days fires raged, leaving behind a desolate urban landscape of burnt cars, broken storefronts, and scorched buildings.

Struggling to regroup after Dr. King’s death, the SCLC made the final arrangements for the Poor People’s Campaign. Five weeks after Dr. King’s assassination, thousands of protestors—the majority of them black—arrived in Washington, DC. There, in makeshift sheds and tents and in drenching rain, they built Resurrection City on the Mall, the site of the March on Washington five years earlier. In early June, the movement suffered yet another blow when Senator Robert F. Kennedy—considered a close ally of the freedom movement—was assassinated shortly after winning the California Democratic presidential primary elections. On June 24, 1968, with Kennedy and Dr. King gone, a saddened and confused nation watched police and public authorities raze Resurrection City.

Although a tragic loss to the movement, it is important for students to understand that social movements are rarely embodied in just one individual and that history is not always linear. As historian Timothy McCarthy notes, “For us to understand the forces of history that move history, we need to be open to the possibility that history doesn’t move in neat line or forward progression. And that is particularly true when we are talking about freedom, equality and progress.” In the final activity of this lesson, students will place themselves within these forces of history by reflecting on their vision for the world and how they might “choose to participate” in order to strengthen their communities, nation, and world.