Laundrymen and Movies

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Global Migration & Immigration

This reading comes from the Facing History & Ourselves study guide Becoming American: The Chinese Experience.

Introduction

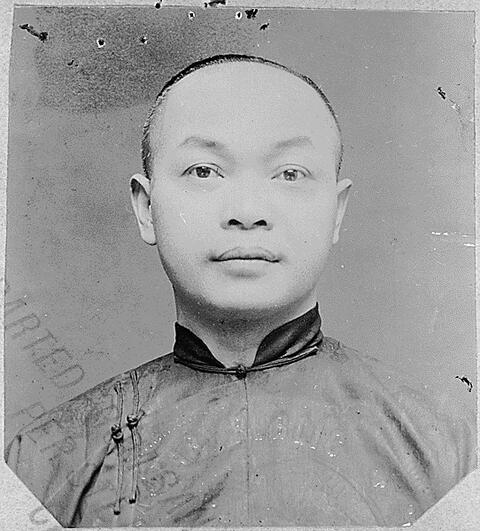

The following excerpt looks at Chinese American life during the 1920s. Historian Henry Yu describes what those years were like for Chinese Americans. He focuses on a single year, 1923:

If you live on the West Coast of the United States and you happen to have come from somewhere in Asia, you live a restricted existence. As an “Asiatic,” a “Mongolian,” an “Oriental,” you are “ineligible for citizenship,” unable to become a naturalized American, and if you are in California, you are forbidden by law from owning land. If you happen to have been born in the United States, you are legally a citizen, but you face widespread discrimination in work, housing, and the law. If you are Chinese, chances are you are male, since exclusionary laws have kept Chinese women out of the country since 1882, and thus fewer than one out of eight people with Chinese ancestry are female. You would find it difficult to live outside of a Chinatown—almost no one except other Chinese would rent or sell to you….

Being considered an Oriental, you find your prospects for prosperity and your choice of employment and housing curtailed by a long history of anti-Asian agitation by labor groups and nativist organizations… The US Congress is just about to pass a series of new immigration laws that will virtually cut off all immigration from Asia. . . . If you are of Asian ancestry in the United States in 1923, you are seen as “alien”— very few people see you as “American.” Even among those who tolerate you and your existence, there is an overwhelming sense that you are an unknown, a mystery, perhaps even inscrutable. 1

What do Yu’s remarks reveal about what it means to be “shoved to the sidelines of American life”?

By the 1920’s, change was coming. Bill Moyers explains, “Some men were able to bring their wives to America. And their children—raised in America—would want very different lives.” A few of those children were willing to defy tradition. Among them was a laundryman’s daughter who decided to become a movie star. Her name was Anna May Wong and she refused to be “shoved to the sidelines of American life.” Although she faced discrimination, Karen Leong says that “it’s a mistake to see Anna May Wong’s career as a tragedy or her life as a tragedy.” How would you assess her career? Was she a tragic figure or was her struggle to overcome the stereotypes that defined her heroic?

How did stereotypes affect the way many other Americans in the 1920s viewed Chinese Americans? The way they viewed Chinese American women? How were those stereotypes reflected in Anna May Wong’s films? What stereotypes shape perceptions today? How are they reflected in current films?

In Part 1 of a three-part memoir published by Pictures magazine in August 1926, Anna May Wong described her childhood in Los Angeles. She focused on an incident that took place when she was just six years old. As she and her sister walked home from school, writes Wong:

A group of little boys, our schoolmates, started following us. They came nearer and nearer, singing some sort of a chant. Finally they were at our heels.

“Chink, Chink, Chinaman,” they were shout¬ing. “Chink, Chink, Chinaman.”

They surrounded us. Some of them pulled our hair, which we wore in long braids down our backs. They shoved us off the sidewalk, pushing us this way and that, and all the time keeping up their chant: “Chink, Chink, Chinaman. Chink, Chink, Chinaman.”

When finally they had tired of tormenting us, we fled for home, and once in our mother’s arms we burst into bitter tears. I don’t suppose either of us ever cried so hard in our lives before or since. 2

When the name-calling continued, the girls were taken out of the public school and placed in the Chinese Mission School. Wong writes, “Though our teachers were American, all our schoolmates were Chinese. We were among our own people. We were not tormented any longer.” The magazine published a second installment of Wong’s memoirs the following month but went out of business before the last installment was published.

Why do you think Wong describes herself as “Chinese” rather than “American”? Why do you think she devoted much of the first installment of her memoirs to an event that took place when she was six years old? What is she trying to tell her fans about herself and other Chinese Americans through this story? What stories might you tell about your childhood?

After Anna May Wong’s death, Frances Chung wrote a poem in her memory. She entitled it “American actress (1907-1961).”

Anna May Wong

L.A. laundry child

phoenix woman

sea green silk gown

ivory cigarette holder

solitary player

on a fast train

through China

speaking Chinese

with American accent 1

Connection Questions

- What does the poet suggest lies behind the stereotypes associated with Anna May Wong? How does she view Anna May Wong—as American, Chinese, or Chinese American?

- 1“American Actress (1907-1961)” by Frances Chung in Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple: The Poems of Frances Chung. Weslayan University Press, 2000, 144.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “Laundrymen and Movies,” last updated March 14, 2016.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.