Visual Essay: Holocaust Memorials and Monuments

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Social Studies

- The Holocaust

- Human & Civil Rights

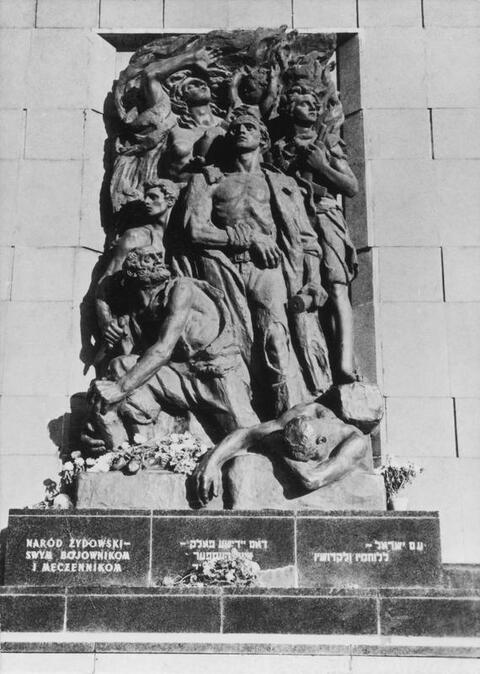

How do we keep history alive in our communities? Which events and people are worth remembering, and why? Memorials and monuments reflect, in part, the ways that communities and individuals have answered these questions. The gallery of images below exhibits a variety of memorials and monuments that have been constructed to remember the Holocaust. The introduction that follows explores the complex questions that memorials raise about how we choose to remember history.

Introduction to the Visual Essay

Across Europe, and even around the globe, people have built memorials to commemorate the Holocaust. Each tries to preserve the collective memory of the generation that built the memorial and to shape the memories of generations to come. This visual essay explores several examples of memorials and monuments to the Holocaust and other histories of mass violence. We use the terms monuments and memorials more or less interchangeably. Some people distinguish between the two, saying that memorials are a response to loss and death and that monuments are more commemorative and celebratory in nature. However, when considering traditional memorials and monuments, there are so many exceptions to these definitions that here we will use the terms more loosely.

Memorials raise complex questions about which history we choose to remember. If a memorial cannot tell the whole story, then what part of the story, or whose story, does it tell? Whose memories, whose point of view, and whose values and perspectives will be represented? Memorials must also respond to the question, “Why should we remember?” Writing of memorials in Germany, Ian Buruma distinguishes between a Denkmal, a monument built to glorify a leader, an event, or the nation as a whole, and a Mahnmal, a “monument of warning.” Holocaust memorials, he says, are “monuments of warning.” 1

Memorial makers must also decide how to express complex ideas in the visual vocabulary available to them. Shape, mass, material, imagery, location, and perhaps some words, names, or dates can communicate a memorial’s message. Legal scholar Martha Minow asks,

Should such memorials be literal or abstract? Should they honor the dead or disturb the very possibility of honor in atrocity? Should they be monumental, or instead disavow the monumental image, itself so associated with Nazism? Preserve memories or challenge as pretense the notion that memories ever exist outside the process of constructing them? 2

Some observers wonder if memorials might have unintended consequences, undermining the memories that they are meant to preserve. Critic James Young has said of memorials, “It’s a big rock telling people what to think; it’s a big form that pretends to have a meaning, that sustains itself for eternity, that never changes over time, never evolves—it fixes history, it embalms or somehow stultifies it.” 3 Young has suggested that memorials might actually let viewers become more passive and forgetful, because they “do our memory work for us.” 4 Can monuments suggest closure when none exists and consequently insulate us from history or anesthetize us rather than engaging and challenging us?

With these concerns in mind, some artists have created “counter-memorials” that are designed to change over time, to create an awareness of something that is missing, or even to disappear, provoking viewers to question, think, and connect more actively. In Kassel, Germany, artist Horst Hoheisel created a counter-memorial on the site of a majestic, pyramid-shaped fountain that had been given to the city by a Jewish entrepreneur; the original fountain was demolished by the Nazis in 1939. Rather than restore it, Hoheisel created an underground fountain that is the mirror image of the one the Nazis destroyed. Hoheisel explained:

I have designed the new fountain as a mirror image of the old one, sunk beneath the old place in order to rescue the history of this place as a wound and as an open question, to penetrate the consciousness of the Kassel citizens so that such things never happen again . . . The sunken fountain is not the memorial at all. It is only history turned into a pedestal, an invitation to passersby who stand upon it to search for the memorial in their own heads. For only there is the memorial to be found. 5

Connection Questions

- As you explore the images in the visual essay, consider what message each memorial conveys. Who created and authorized the memorial? Who is the audience for this message? How is the message conveyed? Whose story is the memorial telling? What might the memorial be leaving out?

- What are some key differences among the memorials pictured in the gallery above? What do they have in common? Which one speaks to you most strongly?

- Memorials have many different kinds of goals, including telling an accurate story of the past, expressing nationalist ideas, honoring life, confronting evil, and encouraging reconciliation. Do you see any of these goals reflected in the memorials in the visual essay? What other goals might these memorials reflect?

- What are James Young’s criticisms of memorials? Do any of the memorials in this visual essay reflect his concerns?

- What memorials and monuments do you pass in your daily life? Do they have an impact on you? Why or why not?

- 1Ian Buruma, The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994), 202.

- 2Martha Minow, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness: Facing History after Genocide and Mass Violence (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1998), 141.

- 3“

- 4James E. Young, “Memory and Counter-Memory,” Harvard Design Magazine, Fall 1999, accessed June 3, 2016.

- 5Quoted in James E. Young, “Memory and Counter-Memory,” Harvard Design Magazine, Fall 1999, accessed June 3, 2016.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Visual Essay: Holocaust Memorials and Monuments," last updated August 2, 2016.