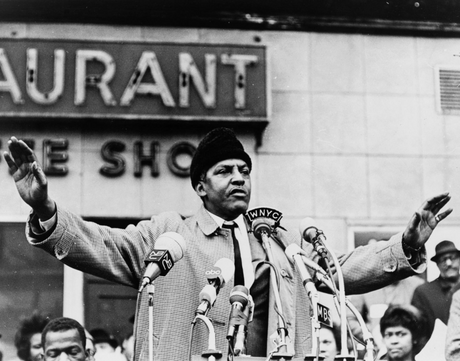

LGBTQIA+ Pride Month every June is an opportunity to explore and amplify the stories of LGBTQIA+ people past and present. But even during Pride Month, we seldom hear stories of LGBTQIA+ people of color. Described as the “unknown hero” of the Civil Rights Movement, Bayard Rustin was the openly gay African American civil rights activist who served as the chief organizer of the historic March on Washington. But why is Rustin so often omitted from the pantheon of African American leaders we learn about in school and pop culture—and how can including his story enrich our understanding of black and LGBTQIA+ history?

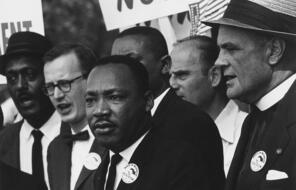

After exploring an array of activist circles in his early years, Rustin worked as a political organizer with the Fellowship of Reconciliation—work that led him to his mentor, legendary labor leader A. Philip Randolph. And this mentorship would thrust Rustin into the center of major debates around who could represent the Civil Rights Movement and why. Convinced that Rustin’s acumen as an organizer could advance the movement, Randolph successfully urged Rustin to meet with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and lend support to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Though Rustin did most of his work behind the scenes, he played a crucial role in helping King adopt a nonviolent philosophy while serving as his special assistant, ghostwriter, and movement strategist.

Though King had read Mahatma Gandhi’s writings, “[i]t was Bayard Rustin, and a few other pacifists,” says scholar Michael G. Long, “who really encouraged Dr. King to accept pacifism as a way of life.” As he became central to King’s inner circle, Rustin would have a defining impact on the vision and strategy of the Civil Rights Movement, championing nonviolent direct action as the most effective means of disrupting racism and violence. But for all of his influence, including his work with the historic Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Rustin remained out of the spotlight and was never permitted to become a highly visible “face” of the movement due to his sexual orientation and former political affiliations.

Rustin’s marginality within the movement reached new heights in 1960 when a powerful opponent targeted his sexual orientation to gain the upper hand over the SCLC. King, Rustin, and Randolph had planned a protest outside of the Democratic National Convention (DNC) that year to challenge the party’s position on civil rights. DNC leadership then asked black congressman Adam Clayton Powell to stop the march, at which point he threatened to leak a fabricated news story to the press alleging an affair between King and Rustin. King subsequently distanced himself from Rustin, leading Rustin to resign from the SCLC.

Despite the pain of betrayal that Rustin faced during this chapter, his activism continued and he would re-enter the fold when King sought to deploy Rustin’s talents once again. Determined to make his next endeavor a success, King brought Rustin on as the chief organizer of the March on Washington—one of the largest protests in U.S. history where King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. Though King and his collaborators knew that they needed Rustin’s unmatched skill, Rustin was kept out of the limelight again.

Though Rustin understood the strategic concerns that led peers to marginalize him within the movement, he recalled later in life that being his whole self in public remained vital throughout his life of activism. “It was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t...I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was part of the effort to destroy me,” Rustin said in an interview released on the Making Gay History podcast. And as the gay rights movement gained momentum in the 1980s, Rustin became a vocal figure.

Though Rustin’s spirit of resistance left an unquestionable impact, many of the pressures that he faced remain decades later. As an openly gay black activist, Rustin was a political liability—a physical manifestation of an inconvenient truth about the Civil Rights Movement: that the group of people whose rights needed to be defended was not merely comprised of straight black men. And yet, the leaders of the movement—shaped by their own prejudices and the desire to gain acceptance from the wider society—were prepared to jettison Rustin, other LGBTQIA+ people, and women to advance the political vision they deemed legitimate and pragmatic.

This is the nature of respectability politics, or what happens when the experiences of some of a marginalized group’s members (e.g. black LGBTQIA+ people) are hushed or simply erased in the pursuit of progress. Facing History explored the pervasiveness of respectability politics in debates about the life and sexual orientation of Rustin’s contemporary, Malcolm X. In both cases, leaders’ attempts to control who could become the face of their movement were central political strategies, but we must ask who is left behind when these maneuvers limit who is able to speak and the stories we feel we can tell about our own histories.

In Rustin, we find the story of an openly gay black man who devoted his career to social change work, and exhibited an abiding pride in who he was even as he faced immense discrimination within and beyond his own communities. We also find a figure who—despite the betrayals and other challenges he faced—remained committed to civic engagement and the long game of promoting social change.

We all lose significantly when the powerful stories of individuals like Rustin are perpetually absent from textbooks, and LGBTQIA+ youth of color suffer greatest when these omissions mislead them into thinking that they do not have a history at all. The need to actively expand the scope of the stories we tell and the protagonists within them remains pressing, and we urge you to join us in this endeavor in the classroom and beyond.