Gathering Anger

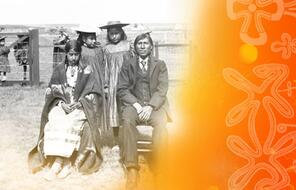

The 1969 White Paper was met with widespread opposition inside and outside of indigenous communities. This opposition would defeat, for the first time, the illusion that the “Indian problem” could be, or should be, assimilated away. Indeed, the 1960s saw the emergence of the anti-war movement and the global rise of a variety of left-leaning movements that focused on individual freedom, equal rights, and faithful recognition of minorities’ identities. Across the border, the US civil rights movement registered remarkable successes in defeating Jim Crow racial policies (laws that enforced racial segregation in the US South since the 1890s). The world also witnessed the growth of the anti-colonial movement and the liberation of many formerly colonized nations. The indigenous leadership was reassured by these trends and linked its struggle with the global fight against imperialism. Additionally, court challenges to legal discrimination against Indigenous Peoples finally gained traction and led to the end of the years of injustice enshrined in the different versions of the Indian Act. 1

Responding with growing anger and assertiveness, indigenous activists rejected the idea of equal treatment before the law as simplistic at best. They argued that it was used to mask decades of accumulated material and political privileges for European Canadians acquired at the expense of Indigenous Peoples. 2 Once again it seemed that the government was trying to assimilate the indigenous population rather than respect their rights and treaties. An infuriated Harold Cardinal, an up-and-coming indigenous activist, wrote a response to the White Paper known as the Red Paper. In it he posed a counter policy whose aim was to restore self-governance and indigenous land titles. Cardinal, in fact, turned the debate around, emphasizing the importance of the Indian Act: “The White Paper Policy said that the legislative and constitutional bases of discrimination should be removed. We reject this policy. We say that the recognition of Indian status is essential for justice. Retaining the legal status of Indians is necessary if Indians are to be treated justly. Justice requires that the special history, rights and circumstances of Indian People be recognized. . . . The legal definition of registered Indians must remain. . . . We want our children to learn our ways, our history, our customs, and our traditions.” 3

Cardinal was by no means in favor of the discriminatory aspects of the Indian Act. But he felt that the act was the last defense against assimilation and the loss of the few rights Indigenous Peoples had. In many ways, the Act was a record of the injustices committed against them.

- 1Alan D. McMillan and Eldon Yellowhorn, First Peoples in Canada, 323–34.

- 2Carole Blackburn, “Producing Legitimacy: Reconciliation and the Negotiation of Aboriginal Rights in Canada,” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13 (2007), 633.

- 3“Foundational Document: Citizens Plus,” Aboriginal Policy Studies 1 (2011), 194.