How Can Music Inspire Social Change?

Music has long been used by movements seeking social change. In the 1950s and '60s, this was particularly true, as successful black and white musicians openly addressed the issues of the day.

During the '60s, popular white singers such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez lent both their names and their musical talents to the American Civil Rights Movement. In fact, music long assisted those working to win civil rights for African Americans. Freedom songs, often adapted from the music of the black church, played an essential role bolstering courage, inspiring participation, and fostering a sense of community.

Andrew Young, former executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, remembered how music helped build bridges between civil rights workers and members of the communities they hoped to organize:

"They often brought in singing groups to movement friendly churches as a first step in their efforts...They knew how little chance they stood of gaining people's trust if they presented themselves as straight out organizers: people were too afraid to respond to that approach. So they organized gospel groups and hit the road."

The Staple Singers belonged to that tradition.

Beginning as a gospel group, they became soul superstars at the height of the civil rights movement. As author Rob Bowman notes in his book Soulsville, U.S.A., "They attempted to broaden their audience by augmenting their religious repertoire with 'message' songs."

Musically and politically, the Staple Singers fit right in at Stax Records, that model of racial collaboration in a time of societal upheaval.

Co-owner Jim Stewart argued, "If we've done nothing more, we've shown the world that people of different colors, origins, and convictions can be as one, working together towards the same goal. Because we've learned how to live and work together at Stax Records, we've reaped many material benefits. But, most of all, we've acquired peace of mind. When hate and resentment break out all over the nation, we pull our blinds and display a sign that reads 'Look What We've Done—TOGETHER.'"

According to lead singer Mavis Staples,

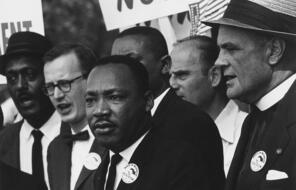

"The songwriters knew we were doing protest songs. We had made a transition back there in the '60s with Dr. King. We visited Dr. King's church in Montgomery before the movement actually got started. When we heard Dr. King preach, we went back to the motel and had a meeting. Pops [Mavis's father, who played guitar and shared lead vocal duties with his youngest daughter] said, 'Now if he can preach it, we can sing it. That could be our way of helping towards this movement.' We put a beat behind the song. We were mainly focusing on the young adults to hear what we were doing. You know if they hear a beat, that would make them listen to the words. So we started singing protest songs. All those guys were writing what we actually wanted them to write. Pops would tell them to just read the headlines and whatever they saw in the morning paper that needed to be heard or known about, [they would] write us a song from that."

Inspired by "Pops" Staples, songwriters Raymond Jackson, Carl Hampton, and Homer Banks penned "If You're Ready (Come Go with Me)" in 1973. Similar in sound to the group's 1972 hit "I’ll Take You There," the song lists specific obstacles to justice.

Recorded after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., both songs build on the "dream" King articulated throughout his career. Seven years after the 1965 Los Angeles Watts Riots, Stax executives outlined plans for a grand concert that would bridge music and activism.

"[The Initial plan] was to feature three acts performing in Will Rogers Park at the Watts Summer Festival site. Over time, this developed into an all-day concert to be staged at the Los Angeles Coliseum on the final day of the Watts Summer Festival featuring virtually every current Stax artist. The artists would give their performances free of charge, Schlitz beer would sponsor the event and thereby offset some of the production costs, and Stax would pick up all other incurred costs. Admission was held to a one-dollar, tax-deductible contribution per person so that virtually anyone in the community could afford to buy a ticket. Even so, several thousand tickets were distributed absolutely free of charge."

Some scholars suggest that the 1972 Wattstax music festival reflected the new-found emphasis on black empowerment, moving beyond legal recognition of equality to a focus on self-determination.

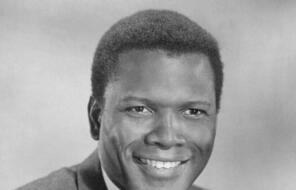

Photo courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music.

The Staple Singers were just one of many Stax artists that participated. Singer Carla Thomas remembered being in Los Angeles during the Watts Riots and said she was "happy to be back and be a part of the rebuilding, instead of tearing something down." Saxophonist Floyd Newman noted that what started as just "another gig" for Stax musicians became a "worldwide thing." One writer declared, "The event marked the first all Black entertainment event of its size and scope ever to be completely Black controlled!" In the end more than 112,000 people attended, making it the second largest gathering of African-Americans in the United States at the time, second only to the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Equality.

Invite students to watch a video of Stax Music Academy performing "If You're Ready (Come Go With Me)" by the Staple Singers:

Then have students answer the following questions independently, in groups, or as a class:

- How does music impact the way people think and act?

- How can music encourage people to participate in their community, their nation, and the world?

- What role can music play in a movement for social change?

- What type of society were the Staple Singers envisioning?

- How did the Staple Singers view the purpose of their music

- Are there contemporary examples of music addressing a social issue?

The lesson plans and videos are part of Facing History & Ourselves' latest teaching resource, Sounds of Change, published in partnership with the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis, Tennessee. The resource's text-dependent questions that accompany both the lyrics and the historical documents are based on the Common Core Anchor Standards for Reading and Literacy in Social Studies. In addition to measuring student understanding of the material covered, the questions will prepare students for the types of questions they will encounter on Common Core State Standards–aligned assessments.

Don't miss out!

- download classroom materials

- view on-demand professional learning

- and more...