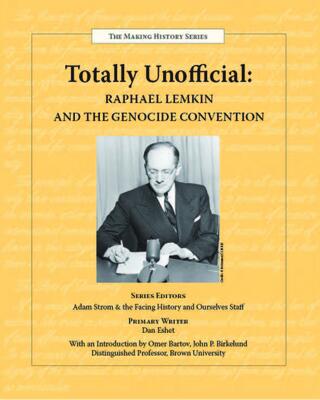

Totally Unofficial: Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Social Studies

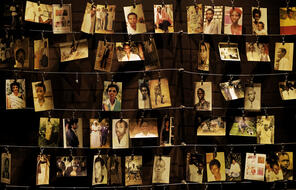

- Genocide

Totally Unofficial: Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention

Purchase

This book is available for purchase from most places you buy books, including major retailers and independent bookstores.

Download a PDF of this resource for free

Born in 1900, Raphael Lemkin devoted most of his life to a single goal: making the world understand and recognize a crime so horrific that there was not even a word for it. Lemkin took a step toward his goal in 1944 when he coined the word genocide—destruction of a nation or an ethnic group. He said he had created the word by combining the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing). In 1948, nearly three years after the concentration camps of World War II had been closed forever, the newly formed United Nations used this new word in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, a treaty that was intended to prevent any future genocides.

This case study of Raphael Lemkin challenges us to think deeply about what it will take for individuals, groups, and nations to take up Lemkin's challenge.

Features include:

- Introduction by genocide scholar Omer Bartov

- Historical case study of Lemkin and his legacy

- Questions for student reflection

- Lesson plans using the case study

- Primary source documents