Developing Character Inferences

Overview

About this Lesson

In the previous lesson, students explored class and social hierarchy in Edwardian England by reading and discussing etiquette manuals and, in An Inspector Calls, by ordering the characters according to their social rank in the Victorian and Edwardian class system. This enquiry not only gave students the opportunity to engage with challenging non-fiction texts and apply contextual information to the content of the play, it also paved the way for reflection about modern social norms and their impact on opportunities, choices, and values. Whilst the value placed on class has diminished somewhat, it still exists. Acknowledging this sometimes invisible societal structure is important as it adds complexity to students’ examination of the relationship between the individual and society.

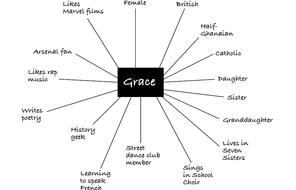

In this lesson, students will turn their focus back to the content of the play and to developing effective analytical skills. They will be introduced to the concept of inferencing and will begin making inferences about the characters and setting in the opening scene of the play, considering what messages Priestley sends to the audience through his use of language, characterisation and development of setting. This will not only prepare students to analyse the play, it will also enable them to think about how they make connections between what they read and hear and the world around them. Explicitly explaining the process of inferencing can be a very empowering process as it helps students reflect on how their minds work when they are reading a text or encountering new information.

The activities in this lesson refer to pages 1–5 of the Heinemann edition of An Inspector Calls.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

Developing Character Inferences

Understanding Class

Understanding Mr Birling

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand