“An Antidote to the Far Right's Poison”: The Battle for Cable Street’s Mural

In March 1983, three artists completed work on the Battle of Cable Street mural, commemorating the historic 4th October 1936 event when thousands of Jewish residents of London’s East End, Irish dockworkers and labourers, Communists, and Labour Party members, among others, united in solidarity against Fascist Sir Oswald Mosley and his parade of Blackshirts, accompanied by hundreds of police officers, when they attempted to march down Whitechapel High Street in London’s East End. The mural, which depicts events from the march and also honours the neighbourhood’s changing demographic and resident Bengali community, has its own turbulent history having been vandalised with racist graffiti on numerous occasions. This article from The Guardian describes how artist Dave Binnington conceived of the original design and why it took almost ten years for the mural to be completed.

. . . Binnington had produced vivid and striking work under London’s Westway flyover, inspired by the Mexican mural artists David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera. He read voraciously about the battle, and both he and Mills interviewed veterans to collect firsthand information. Binnington projected a slide of an early design on to the town hall wall. He recruited another artist, Paul Butler, to produce a series of predella panels across the lower section, narrating the battle.

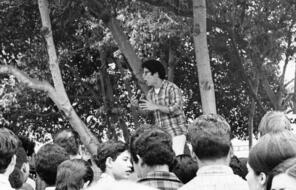

A mural project committee leafleted locals, inviting them to contribute poems, drawings and memories and offering them the chance to appear in the mural. “Just as the crowd in 1936 was made up of local people,” the leaflet stated, “so shall the mural be an image of people living here now.”

Many faces in the mural were taken from newspaper photos of the battle, but the more ethnically diverse group behind a banner on the lower left represents Cable Street’s 1970s residents. By then, few Jews lived there. The Irish remained, but the new fast growing community was Bangladeshi. Like earlier Jewish immigrants they worked in the rag trade around Brick Lane and Cannon Street Road, which crosses Cable Street. Like the Jews, they too were targeted by racists and fascists. The National Front stepped comfortably into Mosley’s boots.

Bangladeshi Nooruddin Ahmed, who came to the East End in his teens, recalls the febrile atmosphere: “Most of Tower Hamlets was a no-go area for Bengalis,” he says. Brick Lane and Cannon Street Road were “the sole places where Bengalis felt relatively comfortable”.

Julie Begum conjures up the fear. “You went to school, you went home, you didn’t hang around. You did your shopping, and you hoped that you were not going to be attacked on your way there or back.”

Britain’s first Bengali MP, Rushanara Ali, settled in the East End with her parents in the early 1980s. As a child, she recalls, “we weren’t allowed to go out and play unsupervised, even right outside, because there was a lot of racism.” In the evening she stood at the window with her mother watching for her father to get home safely from work.

On 4 May 1978, Altab Ali, a 25 year old Bengali machinist, was walking home from work when he was attacked and stabbed to death by a racist gang near Whitechapel Road. There were local elections that day. The NF were contesting 41 seats in Tower Hamlets.

In 1982, the incomplete mural was daubed with six-foot high racist slogans. Binnington was devastated and abandoned the project. Two other artists, Des Rochfort and Ray Walker, helped Butler reimagine and complete the mural. It may look like one dynamic, convulsive, and coherent image, but it was created in sections by three individuals, each with their unique style.

Ten years after the unveiling, as Butler was restoring the weatherbeaten mural, the fascists returned: the British National Party had won a local council seat. Its emboldened supporters paint-bombed the mural and threatened Butler. “I had my tyres slashed and white paint poured all over my car,” he says. “We had to have a police guard. You felt very vulnerable up the scaffolding. You could be shaken off it like an apple on a tree.”

Butler’s further restoration experience in 2011 was less fraught. Local teachers brought students – most of Bengali and Somali heritage – to see the mural and question Butler and Mills. Butler enthuses about how strongly these young people identified with the narrative. Last year, Rachel Burns, a Jewish teacher whose grandparents inhabited the volatile East End of the 1930s, worked on a project centred on the mural, involving four schools, with Jewish and Muslim schools working together. The students, she says, “realised it was not only about racism but also about solidarity”.

Rushanara Ali was 12 when she first visited the mural with her history teacher, but its potency stayed with her. As a student at Oxford, she wrote her first article for the student magazine about the mural. Though it depicts the struggles of Jewish immigrants, she is emphatic that it “belongs to everybody. It is part of us, part of our community’s local heritage.” Jones, whose Jewish mother was an anti-fascist activist in the 1930s, remembers proudly that the mural project was championed by two of Tower Hamlets’ first Asian councillors.

Cable Street forms the boundary of Ali’s constituency. The south side, including the mural, is the territory of Jim Fitzpatrick MP. He marvels at the power of art to communicate “to people who might not be interested in reading history” its central message: that “collective political action, bringing people together, is the antidote against the far right’s poison”. 1

- 1David Rosenberg, “'An antidote to the far right's poison' – the battle for Cable Street’s mural,” The Guardian, September 21, 2016. Reproduced by permission of The Guardian.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “‘An Antidote to the Far Right's Poison’: The Battle for Cable Street’s Mural,” last updated May 4, 2022.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.