Negotiating Peace

At a Glance

Subject

- History

- Human & Civil Rights

- The Holocaust

After the United States entered the war in 1917, the tide turned decisively in favor of the Allies. In September 1918, Germany’s generals informed Kaiser Wilhelm and his chancellor, Prince Max von Baden, that the war was lost. Two months later, the British and French governments demanded that the Germans sign a cease-fire or face an Allied invasion. At 5:10 a.m. on November 11, the Germans signed the document, and at 11:00 a.m. the guns fell silent on the western front. The kaiser had already abdicated, or given up his power, and a new German government awaited a peace treaty that would formally end the war.

The Germans had hoped to negotiate a cease-fire based on principles set forth in a speech given by US president Woodrow Wilson in January 1918. They also hoped those principles would be incorporated into the peace treaty. In his speech, Wilson had identified “fourteen points” he considered essential to a just and lasting peace. They included the removal of the German army from territories it had conquered during the war, an end to secret agreements between countries, open seas, no more barriers to international trade, disarmament, national self-determination for groups that were once a part of the old empires (see reading, Self-Determination), and the establishment of a League of Nations to prevent future wars (see reading, The League of Nations).

However, neither Britain nor France had agreed to Wilson’s Fourteen Points. During the war, the two nations had made secret plans to divide up the colonies Germany had held before the war. They had also made deals with various nationalist groups eager for the independence of those colonies. In addition, much of the war on the western front had been fought in Belgium and France, and both expected Germany to pay for the devastation.

The Allied countries—including the United States, Britain, France, Italy, and Japan—negotiated the peace treaty at the Palace of Versailles in France from January 1919 to January 1920. The final Treaty of Versailles contained 440 articles.

Article 231 of the treaty explained who would pay for the enormous cost of the war and the damage in the war-torn Allied countries:

Article 231

The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies. 1

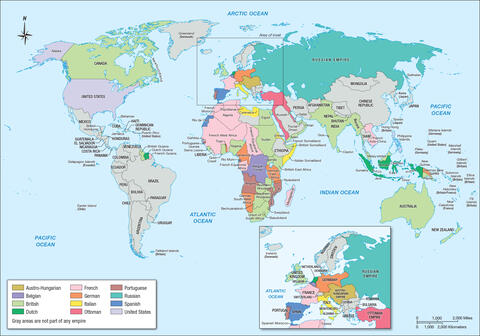

Other portions of the treaty outlined how Germany would pay reparations to other countries. In addition, the treaty stated that Germany would limit the size of its military to fewer than 100,000 soldiers. It also specified new borders for Germany, with the result, as historian David Stevenson notes, that “Germany lost about 13 per cent of its area and 10 per cent of its population in Europe (though most of those transferred were not ethnically German), in addition to all its overseas possessions.” 2 In addition, Germany had to give up all of its colonies abroad. The maps below show the change in Germany’s territory between the pre-war and post-war period. The first map shows the world in August 1914, when World War I began.

World War I hastened the crumbling of several empires, while others retained their global power. Compare the map of the 1920 world, below, to a map of empires in 1914, below. The second shows the world five years later, soon after the war ended.

Germans had no choice but to accept the Treaty of Versailles. The treaty required more concessions from Germany than Wilson’s Fourteen Points had suggested. However, historian Doris Bergen argues that the terms of the Treaty of Versailles were not as harsh on Germany as the terms that Germany had imposed on Russia in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 (see reading, Russia Quits the War). 3 Regardless, many Germans were outraged and believed that the treaty had humiliated their nation.

- 1“The Versailles Treaty, June 28, 1919,” available at the Avalon Project (Yale Law School), accessed March 2, 2016.

- 2David Stevenson, Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 422.

- 3Doris L. Bergen, War and Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust, 3rd ed. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 42. Reproduced by permission from Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

Empires before World War I

Empires before World War I

In 1914, much of the world was dominated by a handful of empires. When fighting broke out that year, the global reach of warring empires ensured a World War.

The World after World War I

The World after World War I

World War I hastened the crumbling of several empires, while others retained their global power. Compare this map of the 1920 world to a map of empires in 1914. See full-sized image for analysis.

Connection Questions

- According to the Treaty of Versailles, who should be held responsible for the war and the damages it caused?

- What do the two world maps show about the way the world changed between 1914 and 1920? Who gained land? Who lost land? Which nations were created by the peace conference at Versailles?

- In the aftermath of a war, who should get to define the terms of peace? Who defined the terms of peace after World War I?

Get the Handout

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Negotiating Peace," last updated August 2, 2016.