Disrupting Public Memory: The Story of the National Day of Mourning

For many Americans, the popular story of the first Thanksgiving often goes like this: in 1621, the Pilgrims had recently arrived in what is today Plymouth, Massachusetts—the traditional lands of the Wampanoag and Massachusett people—and were faced with a cold and bitter winter. The Wampanoag people noticed their plight and generously provided the Pilgrims with the means to survive. To provide thanks, the Pilgrims welcomed the Wampanoags to a harmonious feast. This narrative is shared in classrooms across America every year, has persisted in public memory, and is deeply embedded in the national identity of the United States. However, like many exceptionalist narratives in American history, this story is a one-sided understanding that glorifies colonization and ignores the full truth of history, particularly for the Indigenous People of the United States.

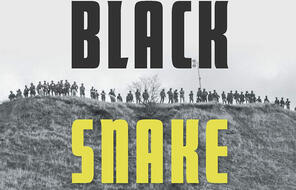

While many historians and activists have worked to disrupt public memory as it relates to the imagined history of Thanksgiving, the true agency of the story lies in the hands of Indigenous communities, who recognize the fourth Thursday of November as a National Day of Mourning. The National Day of Mourning is an annual day of remembrance and protest organized by the United American Indians of New England (UAINE). Held each year on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, the National Day of Mourning provides the space for Indigenous People to speak about their history and the struggles they experience at the hands of the United States government.

The National Day of Mourning began in 1970 as a form of protest to the 350th anniversary celebration of the arrival of the Pilgrims. The 350th celebration was organized to celebrate the glorified, and largely false, narrative of Wampanoag-Pilgrim relations in the 1620s. As part of the celebration, organizers approached Wamsutta (Frank) James, a Wampanoag man, to give an appreciative speech. The speech that James was set to deliver at the celebration was censored because it was not in line with the mythological story celebration organizers were set on sharing. James declined to deliver a scripted speech at the celebration, and instead the suppressed speech was delivered at the first National Day of Mourning.

In the suppressed speech, James shared how the consequences of colonial settlement have impacted the Wampanoag people:

“Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans... Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.”

James’ speech includes the harsh truths for those who have grown accustomed to the narrative of harmony. The reality of the early relations with Indigenous People and the first Thanksgiving in what would become the United States is one marked by epidemics, robbery, and violence. While the suppressed speech was marked by great sorrow and truth, it also speaks of the resilience of the Indigenous People of the Americas and the enduring presence of their language and practices. James explained, “Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians! Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts.”

Every year since 1970, Indigenous People have gathered in Plymouth, Massachusetts to honor their ancestors and protest the oppression many Native Americans continue to face today. This event not only recognizes historically marginalized Indigenous voices, but also brings attention to the history that many Americans continue to willfully ignore. While challenging a narrative that is so deeply embedded in American consciousness can be difficult, we are stewards of this legacy and have the responsibility to face the past and the present so we can develop a more inclusive and accurate understanding of the past. As Frank (Wamsutta) James shared in 1970, “What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail.”

---

When the first colonial settlers arrived in what is now the United States, the land was home to hundreds of diverse Indigenous nations—nations who continue to fight for recognition of their sovereignty to this day.