Introduction: Transition to Democracy

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

A New Start for South Africa | A New Constitution | Seeking Truth and Justice | Symbolism, Sports, and Unity | The Persistence of Economic Inequality | Education | Challenging the “Rainbow Nation”: Xenophobia Against Migrants | The Shadow of Apartheid: Economics and Health | The Marikana Miners' Strike and Massacre | Looking Forward

As negotiations between the National Party and the ANC became public in the early 1990s, South Africans began to imagine a democratic future. Leaders of the anti-apartheid struggle sought to create a government that reflected the country’s diversity, transforming a state long committed to white supremacy into what many began to describe as a “rainbow nation.” Yet the long history of racism and violence that reached a pinnacle during the 40 years of apartheid left many deep legacies and problems. The population remained physically segregated along racial lines, economic inequality was among the worst in the world, and violence had become endemic. Under apartheid, the majority of the South African population viewed the government as a source of disorder, restriction, and violence. Even the election of Nelson Mandela, a widely respected and trusted leader, did not transform people’s attitudes overnight.

As the people of South Africa pushed to rebuild their country, they faced the daunting challenge of addressing the legacies left by apartheid: How could a divided people achieve unity? How could the country’s groups retain their identities while finding new ways to live together and mix peacefully? What would the role of the minority white community be in the new South Africa? How could a population of black South Africans who had suffered for so long finally begin to heal? What should be done about the crimes that had occurred under apartheid? Who should be held accountable? Should the offenders be punished? How could opportunities be created for the millions of people who had been held down by an oppressive state for so long?

South Africans entered the post-apartheid era with newfound empowerment, a visionary leader, and the goodwill of millions of people from around the world. As discussed in this chapter, a democratic and multiracial South Africa has confronted many of the legacies of apartheid and undergone some very important positive transformations—but the country continues to face serious challenges.

A New Start for South Africa

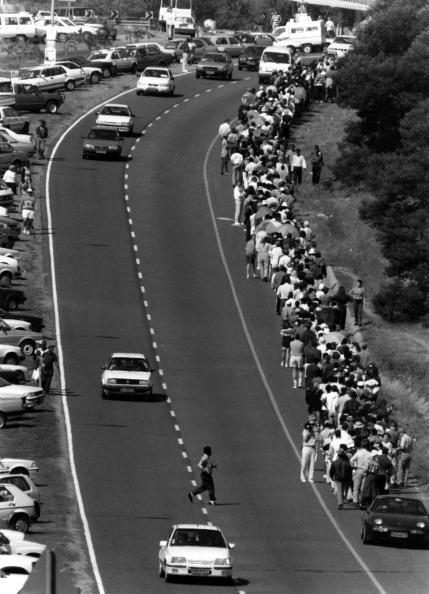

On April 27, 1994, millions of South Africans voted in the country’s first fully democratic elections. As discussed in Chapter 3, the black community was still reeling from government-sponsored violence during the period of transition, but in spite of this, the elections were largely peaceful. For the majority of the population, this was their first opportunity to vote. In the reading South Africa’s First Nonracial Democratic Election, one such voter reflects on the way he processed this change and what the act of voting came to mean. More than 85% of those eligible participated, many standing in line for hours for the chance to choose their own government; the first free and fair elections in South Africa felt like a celebration and a great event for the citizens of the country.

1994 Elections

1994 Elections

Long lines edge the William Nicol Highway, as people wait to vote during the general elections on April 27, 1994 in Johannesburg, South Africa.

In the end, the ANC won 62.7% of the vote, winning 252 seats in the 400-person National Assembly. The National Party won 20.4% of the vote with 82 seats, and the Inkatha Freedom Party won 10.5% of the vote with 43 seats. People did not vote directly for president because South Africa follows a parliamentary system. Instead, people chose a political party that was awarded seats in the National Assembly on a proportional basis. As the majority party in the National Assembly, the ANC chose Nelson Mandela as president.

On May 10, 1994, in a ceremony that filled people across South Africa and around the world with hope, Nelson Mandela was sworn in as president. He was not only South Africa’s first black president but also the first president chosen in competitive, free, and fair elections. In his inaugural address, Mandela declared:

We have triumphed in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of the millions of our people. We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity—a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world. . . .

The time for the healing of the wounds has come.

The moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come.

The time to build is upon us. . . . 1

A New Constitution

Work on a permanent constitution began on May 9, 1994, almost immediately after the transition to democratic rule. The interim document required that the Constitutional Assembly, made up of the 400 members of the National Assembly and 90 members of the National Council of Provinces, approve a constitution by a two-thirds majority. With this structure, the National Party could not veto changes, as it accounted for just over 20% of the legislature. Additionally, the ANC could not make changes on its own; it would need to work with other parties. Most of the drafting of the constitution was done by a constitutional committee made up of 44 members of parliament drawn proportionally from the seven largest political parties. A Constitutional Court oversaw the drafting of the document, ensuring that it complied with the 34 principles that could not be eliminated from the interim constitution, due to terms negotiated during the transition.

During this process, politicians debated the relationship between provincial and central governments, the guarantee of representation for minority parties, land reform, the death penalty, and limits on speech. 2 Cyril Ramaphosa, a veteran of the ANC who would later become president of South Africa, presided as chair of the Constitutional Assembly. Roelf Meyer, a member of parliament since 1979, was lead negotiator for the National Party. Meyer hoped to create a permanent power-sharing arrangement to guarantee National Party control over legislation, thus allowing the white population continuing disproportionate political influence. Meyer was unsuccessful in this goal; the day after parliament approved the new constitution, Meyer’s party withdrew from the Government for National Unity, where they had held several ministerial posts and de Klerk had served as deputy president. 3

During the drafting process, the government began a massive outreach program modeled on the Freedom Charter process to gain insight from the public on what they wanted included in the constitution. The program involved over 400 community workshops and garnered two million letters and petitions from the public. “It was the first time in our history that politicians have gone to the people without playing politics or asking for votes,” observed Hassen Ebrahim, chief executive of the Constitutional Assembly. “I hope it's a lesson that will be pursued in our politics.” When a series of nine big public meetings were held early in 1995, one petitioner advocated for a constitutional right to more libraries, and a memorandum appended to the final constitution described it as “the collective wisdom of the South African people.” 4

The final constitution was approved by the Constitutional Assembly on May 8, 1996. After a period of revision, it was certified by the Constitutional Court on December 4, 1996, and approved by President Mandela on December 10. 5 The Assembly chose this date because it had been recognized in 1950 by the United Nations as Human Rights Day. The presidential signing ceremony took place in Sharpeville, recalling one of the seminal events in the struggle against apartheid. At the ceremony, Mandela declared, “Out of the many Sharpevilles which haunt our history was born the unshakeable determination that respect for human life, liberty and well-being must be enshrined as rights beyond the power of any force to diminish. These principles were proclaimed wherever people resisted dispossession, defied unjust laws, or protested against inequality. They were shared by all who hated oppression, from whomsoever it came and to whomsoever it was meted.” 6

The preamble of the constitution acknowledges the suffering and injustice of the past while conveying a hope for a just, democratic, and united future. To emphasize this commitment, the word democratic appears three times within the preamble itself. The constitution continues in 14 thematic chapters, written in accessible prose and translated into the 11 official South African languages. These chapters focus on such topics as basic rights, elections, the composition of legislative bodies, the organization and function of courts of law, national finance, and national security. The constitution also upholds the rights of distinctive ethnic communities (those sharing “a common cultural and language heritage”) to self-determination (article 235), the recognition of traditional leaders (articles 211 and 212), and the obligations of different organs of state to “preserve the peace” and “co-operate with one another” (article 41). The first chapter of the constitution states:

The Republic of South Africa is one, sovereign, democratic state founded on the following values:

a. Human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.

b. Non-racialism and non-sexism.

c. Supremacy of the constitution and the rule of law.

d. Universal adult suffrage, a national common voters roll, regular elections and a multi-party system of democratic government, to ensure accountability, responsiveness and openness. 7

The South African constitution is widely recognized as including the most extensive human rights guarantees of any constitution in the world, as it places its list of 32 rights before any mention of the structure of government. 8 This section is a careful monument to the achievement of those who campaigned for equality. Included among the rights guaranteed by South Africa’s constitution are equality, freedom from discrimination (including bigotry based on sexual orientation or age), a right to human dignity, freedom of religion and expression, and the right to form and join trade unions. Chapter 9 of the constitution, which defines equality before the law, specifies a long list of protected categories: “The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.” 9 This provision made South Africa the first constitution in the world to guarantee gay and lesbian rights, which offered new freedoms and led to other important legal gains, as described in the reading The Equality Clause: Gay Rights and the Constitution.

Many of the provisions in the constitution’s bill of rights are direct responses to practices of the apartheid state. For example, the apartheid state commonly detained individuals it suspected of opposing apartheid without charging them, and many of these individuals were tortured. In response, Article 12 of the constitution guarantees “freedom and security of the person.” It states that people cannot be arbitrarily detained and that they have a right “to be free from all forms of violence from either public or private sources” and a right “not to be tortured in any way.” 10 Article 35 outlines in great detail the rights of those arrested, accused, or detained. No law can protect people from harm, but here is a body of laws whose enforcement will ensure that the horrors of the past are not repeated. The reading The South African Constitution offers a closer look at the constitution’s preamble, which frames these ideas, and the bill of rights—perhaps the most comprehensive in the world.

Seeking Truth and Justice

In the negotiations for transition, one major debate centered around accountability for the violence used to enforce apartheid. The ANC leadership wanted to publicize the facts of apartheid violence and bring perpetrators to justice, but de Klerk had promised amnesty to the security forces. A compromise was conceived by Dullah Omar, a veteran of the anti-apartheid struggle, who became the minister of justice following the 1994 elections. Omar proposed public hearings that would allow open discussion of the violence surrounding apartheid. These hearings would include the possibility of amnesty for those who fully disclosed their crimes and could prove that they had a political motive.

- 1Nelson Mandela, “Nelson Mandela’s 1994 Inauguration Speech” (transcript), Pretoria, South Africa, May 10, 1994), BET website.

- 2“Making the Constitution: South Africa,” The Economist, January 13, 1996, 42.

- 3Padraig O’Malley, “Full House,” O’Malley: The Heart of Hope website, “Post Transition (1994–1999): Constitution Making” section, Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, accessed July 21, 2015.

- 4Padraig O’Malley, “A Very Distant Deadline,” O’Malley: The Heart of Hope website, “Post Transition (1994–1999): Constitution Making” section, Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, accessed July 21, 2015; “Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996—Explanatory Memorandum,” South African Government website, accessed July 22, 2015.

- 5Recent Developments, “Making the Final Constitution in South Africa,” Journal of African Law 41, no. 2 (1997): 246–47; “The Certification Process,” Constitutional Court of South Africa website, accessed July 21, 2015.

- 6“Speech by President Nelson Mandela at the Signing of the Constitution,” Polity.org, accessed July 21, 2015.

- 7Government of South Africa, “Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996,” South African Government website.

- 8Ian Millhiser, “What Americans Can Learn from the Constitution Nelson Mandela Signed,” December 6, 2013, ThinkProgress website, accessed July 21, 2015.

- 9Millhiser, “What Americans Can Learn from the Constitution Nelson Mandela Signed.”

- 10Constitution of South Africa, Chapter 2: Bill of Rights, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development of South Africa website, accessed May 23, 2018.

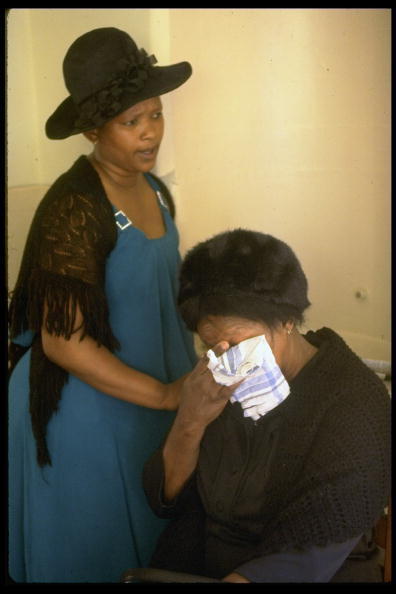

Ntsiki Biko Consoles her Mother-in-Law Alice Biko

Ntsiki Biko Consoles her Mother-in-Law Alice Biko

Nontsikelelo 'Ntsikie' Biko (L), widow of South African civil rights activist Steve Biko, consoles his mother Alice (R) during the investigation into his death from beatings administered by the South African Security Police.

In 1995, the new parliament established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC investigated and recorded gross violations of human rights committed in South Africa and beyond its borders between 1960 and 1994. The TRC focused on both supporters and opponents of apartheid, allowing the process to appear balanced and fair. Perpetrators of human rights violations could provide testimony and apply to the Amnesty Committee, one of three TRC committees. Victims were also encouraged to submit testimonies to the Human Rights Violations Committee. Once such testimony had been corroborated, some victims were eligible for reparations, or financial payments from the government, which were administered by the Reparations Committee. The organizers explained, “These measures cannot bring back the dead, or adequately compensate for pain and suffering, but they can improve the quality of life for victims of gross human rights violations and/or their dependents.” 1

Omar emphasized that in his view, the aim of the TRC was not forgiveness: “Forgiveness is a personal matter. However, bitterness can only exacerbate tensions in society. By providing victims a platform to tell their stories and know the destiny of their loved ones, one can help to achieve a nation reconciled with its past and at peace with itself.” 2 The TRC mandate said that “to achieve unity and morally acceptable reconciliation, it is necessary that the truth about gross violations of human rights must be: established by an official investigation unit using fair procedures; fully and unreservedly acknowledged by the perpetrators; made known to the public, together with the identity of the planners, perpetrators, and victims.” 3 Amnesty would be granted only to those who applied for it and fully disclosed their misdeeds. The crimes were then judged in proportion to their political aims. Rulings on amnesty were made by the commission.

In typical prosecutions, the focus is usually on perpetrators. At the TRC hearings, the co-chairs, archbishop Desmond Tutu and Alex Boraine, focused on the victims, their families, their suffering, and the crimes committed against them as human beings. As Boraine, who served as vice president of the commission, said at an international conference, “To ignore what happened to thousands of people who were victims of abuse under apartheid is to deny them their basic dignity. It is to condemn them to live as nameless victims with little or no chance to begin their lives over again.”

The ANC and most black South Africans wanted to bring perpetrators to justice, but because de Klerk, who in the early 1990s was still president, had promised his security forces amnesty, a compromise was reached. Perpetrators would be granted amnesty, as individuals, but only if they met two criteria: 1) they publicly told the full truth about what they had done, and 2) their deeds had been carried out for a political purpose. To encourage perpetrators to come forward, the state had the power to charge with crimes those who had not received amnesty.

In court-like proceedings, the TRC began taking evidence in 1996. For two years, the commission chair collected testimony from both victims and perpetrators and held hearings throughout the country, many focused on specific instances of violence. 4 Over 7,000 people applied for amnesty, and over 21,000 people submitted victim statements. Some 2,500 perpetrators of political crimes came before the commission, a small percentage relative to the number of people who committed crimes and the mass violence that occurred. Televised public hearings and radio coverage gave victims the opportunity to share their stories publicly. Some were able to confront the worst of apartheid’s agents. Thousands of victims and survivors were also allowed to air their grievances. 5

The entire South African community was able to follow the proceedings. A weekly television show summarized the testimony in the TRC hearings of the previous week, allowing a wide audience to learn about the various crimes that had occurred during the apartheid era. Importantly, radio, a medium used by the majority of South Africans, also carried the hearings, as did newspapers and other print media. In addition, there was a dedicated website that posted transcripts. These efforts were not just about sharing the TRC’s work; they were also explicitly aimed at creating transparency, a crucial element of democracy. For the first time, South Africans were allowed to see such processes at work. Unlike prior truth commissions in other countries, which often amounted to back-room amnesty deals, the South African TRC became both a process by which the young democracy could address the violent past and a medium for democratization.

- 1Truth and Reconciliation Commission, “A Summary of Reparation and Rehabilitation Policy, Including Proposals to Be Considered by the President,” Republic of South Africa, Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, accessed July 31, 2015.

- 2Antjie Krog, Country of My Skull: Guilt, Sorrow and the Limits of Forgiveness in the New South Africa (New York: Times Books, 1999), 9.

- 3“Explanatory Memorandum to the Parliamentary Bill,” South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, accessed June 26, 2016.

- 4Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, “Truth and Justice: Unfinished Business in South Africa,” Traces of Truth website, accessed 4 June 4, 2015.

- 5Therese Abrahamsen and Hugo van der Merwe, “Reconciliation through Amnesty? Amnesty Applicants’ Views of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, accessed July 31, 2015.

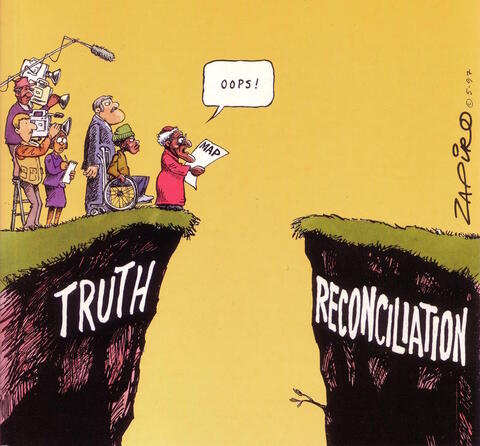

Archbishop Tutu and the Chasm

Archbishop Tutu and the Chasm

Standing at the edge of a cliff labeled ‘Truth,’ Archbishop Desmond Tutu clutches a blank map. Behind him stand a perpetrator, a victim, and members of the media. A deep chasm separates them from the cliff labeled ‘Reconciliation.’

Giving a voice to victims was one of the most important aspects of the TRC. Across the country, victims came forward in town halls to speak of the atrocities they had personally faced or to speak for their loved ones who had been killed or who had disappeared. Many acknowledged the importance of finally having a space to discuss their personal histories. Mzukisi Mdidimba, who was beaten by police at the age of 15 while in solitary confinement, spoke of what it meant that his story had finally been told. He remarked, “When I have told stories of my life before, afterward I am crying, crying, crying . . . This time, . . . I know [that] what they have done to me will . . . be all over the country. I still have some sort of crying, but also joy inside.” 1 The reading The Truth and Reconciliation Commission includes an extended example of TRC victim testimony, from the wife of a political leader murdered by security police in 1985.

At the conclusion of the hearings, the TRC compiled a six-volume report of its findings and submitted it to President Mandela in October 1998. In total, there were 1,188 days of hearings; 7,112 people petitioned for amnesty, 5,392 were refused, and 849 were granted amnesty. Two more volumes were submitted later that assessed the work of the TRC. These later reports focused on the cases that the TRC had not been able to investigate sufficiently and provided recommendations for the future. 2 Critics of the TRC have claimed that the process did not succeed in bringing reconciliation to South Africa because the hearings focused too much on individual cases while failing to look at the broad system of inequality, because victims who participated in the process received too little emotional support, and because the reparations were very slow in coming and were ultimately far too small. The reading Examining Weaknesses of the TRC elaborates on some of these criticisms. In an analysis of the TRC, Graeme Simpson writes:

There is a grave risk that out of the testimonies and confessions of a few, a truth will be constructed that disguises the way in which black South Africans, who were systematically oppressed and exploited under apartheid, continue to be excluded and marginalised in the present. The sustained or growing levels of violent crime and antisocial violence, which appear to be new phenomena associated with the transition to democracy, are in fact rooted in the very same experiences of social marginalisation, political exclusion and economic exploitation that previously gave rise to the more ‘functional’ violence of resistance politics. 3

In their 2017 Reconciliation Barometer, the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation reported that “most South Africans feel that reconciliation is still needed, and that the TRC provided a good foundation for reconciliation in the country.” Reconciliation may take the form of an ongoing process rather than something fully achievable—one that must reach deep and wrestle with a public or national morality, according to the bishop in the reading A Need for a Moral Bottom Line. The commissioners of the TRC often said that in order to build a more unified society, first truth is necessary, and only then can come reconciliation. This approach is known as restorative justice, as distinct from retributive justice. The latter is the more common approach for prosecutions and trials and was the model for the Nazi war crimes tribunal at Nuremberg.

The TRC is widely viewed as a success, although an imperfect one. Many countries have since used the TRC as a model for addressing their own painful recent pasts, including Peru, Sierra Leone, and Canada, which held a truth commission to deal with the legacy of abuses against First Peoples. In the US, the city of Greensboro, North Carolina, held a TRC in order to respond to the killing of five anti-Klan demonstrators in 1979. And in Maine, the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth & Reconciliation Commission held hearings to learn the truth about what happened to Wabanaki children and families involved with the state’s child welfare system.

What else did the TRC achieve? One notable accomplishment was a contribution to the prevention of deniability, something all countries must consider in the wake of mass violence. By building a historical record based on testimony and investigation of massive human rights violations committed during apartheid, the TRC placed apartheid at the center of South Africa’s history. South Africa further emphasized a focus on the past and historical memory through early post-apartheid efforts to create institutions like the District Six Museum, the Apartheid Museum, and the site of the Constitutional Court, which was once one of South Africa’s most notorious prisons.

Symbolism, Sports, and Unity

To make this new South Africa successful, President Mandela understood that he needed to bring people along on this journey into the unknown by appealing to what mattered to them. He needed to help all South Africans see him as their president and to feel as if they were part of the new South Africa. While in prison, Mandela had recognized the importance of bonding with Afrikaners through their culture. What could be better as a means of bonding than sports? The love that many Afrikaners had for rugby offered a perfect opening. In 1995, South Africa was scheduled to host the Rugby World Cup. Until that time, rugby in South Africa had been seen as a sport for white people. Many black South Africans viewed Afrikaner support for rugby as another lingering legacy of apartheid; some even rooted against the national team, partly because very few black players took the field for the Springboks, the South African national team.

- 1Susie Linfield, “Trading Truth for Justice? Reflections on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” Boston Review: A Political and Literary Forum, accessed May 23, 2018.

- 2“Amnesty Hearings and Decisions,” Truth and Reconciliation Commission website.

- 3Graeme Simpson, “Repairing the Past: Confronting the Legacies of Slavery, Genocide, & Caste,” Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University, New Haven, CT, October 27–29, 2005.

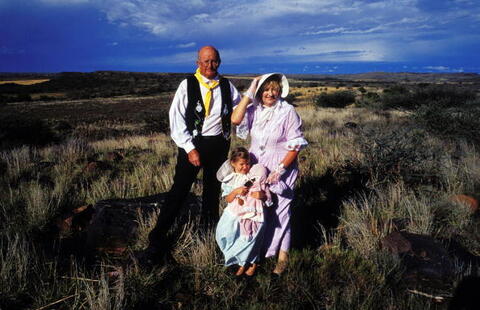

All White Community in South Africa Holds Onto Its Past

All White Community in South Africa Holds Onto Its Past

A family dressed in traditional Afrikaner clothing pose during a holiday celebration commemorating ‘the Battle of Blood River,’ on December 16, 2003 in Orania, Northern Cape province, South Africa.

Prior to 1994, many anti-apartheid activists had supported a boycott on South African sports as a tool of the anti-apartheid movement, infuriating Afrikaners. When the Springboks toured New Zealand in 1981, for example, many New Zealanders protested. This inspired activists to pressure New Zealand to cancel plans to play in South Africa, a campaign that prevailed in 1985. An international boycott of South African rugby began shortly thereafter.

Mandela, who needed the support of Afrikaners as he prepared to negotiate with de Klerk, saw an opportunity. He decided that bringing an end to the Springboks rugby boycott would help with his larger project. The South African team once again faced New Zealand in August 1992. Although the stadium had prohibited apartheid symbols at the game, the national anthem, “Die Stem,” seen by many black South Africans as another symbol of apartheid, was boisterously sung and the old flags were waved. Mandela, however, did not give up hope that sports could be used to help bring South Africa’s people together. In June 1994, with the Rugby World Cup scheduled to begin the following May, Mandela met with Francois Pienaar, the Springboks’ captain, to convey his determination to do all he could to help bring the trophy home. After the meeting, Pienaar and his teammates were convinced that one thing they could do to help build bridges was to learn the new South African national anthem, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Pienaar recalls, “As a matter of historical fact, the Springboks weren’t reluctantly forced to sing the new anthem, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, with the Xhosa words . . . It was something we badly wanted to do ourselves and we organised our own singing lessons before the World Cup. I loved singing it—what an anthem—though I was so emotional in the final I just couldn’t get any words out and had to bite my lip hard to stop cracking up.” 1 Also symbolic of growing tolerance was the song “Shosholoza,” translated as “make way,” “move forward,” or “travel fast,” which was originally sung by the black migrant workers who worked in the gold mines around Johannesburg. It was the longtime anthem at soccer matches, where spectators were mostly black, but was adopted as the new Rugby World Cup song.

Before the first match of the 1995 Rugby World Cup in Cape Town, Mandela made a surprise visit to the startled Springboks team. He explained to them the great service they would be doing for their country by promoting unity. When he finished, the players offered Mandela a green Springboks cap, which he immediately put on. Pienaar later recalled how, at that moment, Mandela won the team’s hearts. In the match, the Springboks were unbeatable: first they overwhelmed the reigning champions, Australia, and then they beat Canada and then France in the semifinal. On the day of the final against New Zealand, Mandela telephoned Pienaar to wish the Springboks good luck. The green jersey and cap that Mandela decided to wear that day, for so long closely associated with apartheid, now symbolized a bond between white and black South Africans.

Only a year after assuming office, Mandela stepped onto the Ellis Park Stadium field before a hushed crowd. As the players prepared to run down the tunnel to the field, they could hear the largely Afrikaner crowd slowly begin to chant and eventually erupt into deafening cheers. The former captain of the Springboks described the scene that greeted him:

I walked out into this bright, harsh winter sunlight and at first I could not make out what was going on, what the people were chanting. Then I made out the words. This crowd of white people, of Afrikaners, as one man, as one nation, they were chanting, ‘Nel-son! Nel-son! Nel-son!’ Over and over . . . and, well, it was just . . . I don’t think I’ll ever experience a moment like that again. It was a moment of magic, a moment of wonder. It was the moment I realised that there really was a chance this country could work. 2

Kobie Coetsee, minister of justice and prisons, later said, “It was the moment when my people, his adversaries, embraced Mandela.” 3

Two hours later, with a word of gratitude, saying, “Thank you for what you have done for our country,” Mandela proudly shook Pienaar’s hand and handed him the trophy, sealing a bond between white and black South Africans. The Springboks captain is said to have replied, “No, Mr. President. Thank you for what you have done.” Coming at the start of an era in which the country would be seeking some shared sense of national identity—a unique and ongoing challenge, as discussed in the reading Creating a Shared Identity for a Democratic South Africa—such a show of unity carried particular weight.

The Persistence of Economic Inequality

Apartheid left a particularly challenging legacy of vast economic gaps between the historically white rich and the mostly black poor. At the most fundamental level, apartheid was a system designed to protect the economic interests of whites and subsidize their lifestyle by limiting competition and suppressing the wages of black South Africans. Government services for whites were extensive, while those for blacks were quite limited. While whites received free education in excellent government schools and world-class healthcare in government hospitals, expenditures on education and health for black South Africans was minimal, resulting in poor schools and substandard healthcare.

As discussed in Chapter 3, South Africa’s political transition was negotiated on the central compromise that it include an agreement to allow whites to maintain their economic position. The National Party was willing to transfer political power to the majority only if whites were allowed to retain control of their land and industries. Some critics of this compromise have argued that the failure to confront the economic consequences of white domination has meant that the transition was only a political one and ultimately failed to end the apartheid economic system. Steven Friedman, a white South African journalist and scholar, later wrote, “While there is no doubting the profound changes which the end of apartheid has produced, it could well be argued that . . . the transition did not encompass the fundamental shift in social and economic power relations which the end of apartheid was meant to produce.” 4

The economic alternatives available to the ANC were limited not simply by the negotiated settlement but also by domestic and international economic constraints. Levying too steep of a tax on the rich population would predictably have driven them to move their wealth outside of South Africa, undermining the economy. The ANC was further constrained by the necessity of attracting critical foreign investment. South Africa shifted to majority rule at a time when the concept of “neoliberal” economics was at its height internationally. Neoliberalism holds that economies do best when the role of government in the economy is limited. Advocates of neoliberalism argue for eliminating restrictions on imports, opening the economy up to international investment, and cutting back on social services. The new ANC-led government thus faced considerable international pressure to limit government spending at the very time when the new leaders were hoping to vastly expand the provision of services to the country’s poor. 5

In 1994, the ANC proposed its first economic policy, called the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). This policy focused on trying to redistribute wealth to the country’s poor, particularly through building infrastructure—providing housing, water, electricity, schools, and hospitals. Yet the success of RDP was limited by budget constraints; the regime did not raise the money that it needed to follow through on its promises. In 1996, RDP was replaced by a new policy: Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR). Although the name included the word “redistribution,” GEAR was in fact a more neoliberal economic program focused primarily on attracting international investment and expanding the South African economy, in the belief that economic growth would ultimately benefit all South Africans. The government continued to invest in developing the infrastructure, but its main focus was on economic growth. 6

While the South African economy has experienced growth and policies have had some success in reducing poverty, the gap between the rich and poor has actually increased. The economic gap continues to fall largely along racial lines. Scholar Elke Zuern writes:

The World Bank reported . . . that the top 10 percent of the population receives 58 percent of the country’s income, while the bottom 50 percent receives less than 8 percent. . . . From 1995 to 2008, white mean per capita income grew over 80 percent, while African income grew by less than 40 percent. Poverty remains overwhelmingly black: In the poorest quintile of households, 95 percent are Africans. Members of this segment of the population struggle to feed their families, allocating more than half of their total expenditure just to food. At the other end of the scale, almost half of the wealthiest 20 percent of households are white, even though whites make up less than 10 percent of the total population. 7

Affirmative action policies have helped to open up employment opportunities for Africans, “coloureds,” and Indians, but these policies have above all benefited those with higher education, who have taken over many government jobs and have gained opportunities as doctors, lawyers, and teachers. The policy of Black Economic Empowerment, adopted by the government in 2007, encouraged businesses to open up opportunities for investment by members of formerly disadvantaged groups. Again, however, these policies primarily helped those who already had some means; the poorest black South Africans did not have the capital to invest in businesses. With legal segregation eliminated, many of the Africans, Indians, and coloureds who could afford to do so moved into formerly white neighborhoods. Today, white South Africans remain the wealthiest population and the poorest are overwhelmingly black South Africans. 8 As a result of the economic polarization there, writer and journalist Hein Marais portrays South Africa as a “two-nation society,” where a wealthy nation and a poor nation exist together side by side in the same territory. 9

Education

Article 29 of the 1996 constitution of the Republic of South Africa declared that “everyone has the right to a basic education” and that schools could no longer discriminate on the grounds of race. The new democracy was determined to go far beyond the bare-bones, far-too-basic schooling that black South Africans had long received. Education had been one of the tools of apartheid, with unequal schools teaching a curriculum that supported the policies and historical narratives of white supremacy. While the central government had previously determined what type of curriculum and what language of instruction would prevail in all of the nation’s schools, under the new constitution, those questions would be determined by local considerations. 10 Still, a massive centralized apparatus—divided in 2009 into a Department of Basic Education and a Department of Higher Education and Training—came to sit atop nine provincial offices of education; education now receives a larger slice of the national budget than does any other sector. 11

While education has seen improvement in some areas, it remains one of the great challenges faced by the government. To undo the damage done by apartheid to the educational system, teachers would need more than money. They would need improved school buildings, new curricula, and better training, as great gaps exist between the facilities serving the rich and the poor. As a senior lecturer at the University of South Africa pointed out, “Almost 80% of schools in the black townships in rural and farm areas have neither basic infrastructure, such as decent classrooms and libraries, nor basic services including clean running water and electricity. They don’t have the required number of qualified teachers or functioning school governing bodies. They report pass rates of less than 30% on required school exit exams. Media reports have highlighted the plight of primary school children who were learning under trees in rural areas of Limpopo province.” 12 Students in primary school continue to perform poorly on tests of literacy and numeracy, and far too many students lack textbooks. Only 12% of black South Africans go to college.

Since apartheid was dismantled, South Africa has seen at least four waves of curriculum reform. First, in keeping with the National Education Policy Investigation, offensive language and content—particularly concepts that reflected and promoted the racist ideas behind apartheid—were purged. Some critics argue that despite good intentions, this was at best a halfhearted effort aimed at furthering reconciliation. Then, during the late 1990s, “values” became the key term, and reformers looked for ways to open the curriculum to include a reflection on ethics—ostensibly the basis of a true democracy. 13

In 1997, while the Truth and Reconciliation Commission continued its work, the Department of Education initiated a major curriculum reform called Curriculum 2005. While some lauded the efforts, critics now point to the short shrift given to history under this plan, and some decry the curriculum as “advocating collective amnesia” for the crimes of apartheid. 14

The appointment of Kader Asmal to the post of minister of education in 1999—a role he would hold until 2004—marked a break with precedent. Asmal had been involved in designing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and he had strong feelings about the need to come to grips with the past. Under Asmal, a working group from the Department of Education produced a report titled Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy (2001). Among the principles underlined early in the report was “putting history back into the curriculum.” This was “essential in building the dignity of human values within an informed awareness of the past, preventing amnesia, checking triumphalism,” and more. 15 The education department set up a specific Race and Values Directorate whose task was to ensure that the curriculum and classrooms became spaces where values and democratic citizenship were addressed. The Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy shaped the Revised National Curriculum Statement that began to be rolled out in schools across the country in 2003. Four years later, Johan Wassermann, the head of the Department of History and Social Studies Education at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, lauded the new content in history books for including “a range of different voices that were silenced in the past.” He believed that the new curriculum would provide students with the opportunity to “see the world through the eyes of someone else. What does it mean to have been a policeman and also a protester during the 1976 Soweto uprising? You are attempting to understand, as opposed to saying that this side is bad and that side is good.” 16 These lessons are part of the ongoing challenge for nations in facing the most difficult moments of their histories—lessons that are both more urgent and, in some ways, more difficult in countries where the wounds of the past are still fresh. For a sense of how South Africans discuss educational and other forms of inequality, see the Antjie Krog reading, Overcoming the Past and Becoming a Single Nation.

Challenging the “Rainbow Nation”: Xenophobia Against Migrants

Since 1994, migration into South Africa has increasingly become an additional challenge facing the country. The exact number of migrants is unclear, as many arrive undocumented. It is estimated that between 1 and 3 million refugees have come to South Africa from other African countries seeking work and opportunity; many have fled violence and persecution in their country of origin. This influx of refugees and immigrants has led to an increase in xenophobia and, especially in townships, xenophobic violence. Townships are ripe grounds for the development of xenophobia, as these are areas where the majority of people live in difficult conditions and where poor newcomers will first try to find homes.

Xenophobia in South Africa has been attributed to many root causes, including fear, frustration with the pace of change, and a culture of violence that is a legacy not only of apartheid but of the transition itself. There is very little evidence to show that the influx of refugees has led directly to an increase in South African unemployment or decreased access to housing. In spite of a lack of evidence, however, many poor and unemployed South Africans believe that migrants will take or compete for jobs and resources.

The violence against migrants has been horrific. On May 18, 2008, in an East Rand township called Ramaphosa, anti-African sentiments erupted in violence. As a mob attacked a group of immigrants, one man was set ablaze. His scorched body was not identified for two weeks. Pictures of the burning man, who was finally identified as Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave of Mozambique, hit media outlets the next day. More xenophobic violence against immigrants from African countries ensued. Thousands were forced from their homes. The message was loud and clear. 17 Nhamuave and other foreigners who came in search of work, even for meager salaries, were not welcome in South Africa. 18

- 1Brendan Gallagher, “Former South Africa captain Francois Pienaar recalls the day no one fluffed his lines,” The Telegraph, January 29, 2010.

- 2Quoted in John Carlin, Invictus: Nelson Mandela and the Game that Made a Nation (London: Penguin Books, 2008).

- 3Quoted in Peter Hain, Mandela (London: Hachette, 2010).

- 4Steven Friedman, “Before and After: Reflections on Regime Change and Its Aftermath,” Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa no. 75 (2011): 4–12.

- 5Michael MacDonald, “The Political Economy of Identity Politics,” The South Atlantic Quarterly, Fall 2004.

- 6MacDonald, “The Political Economy of Identity Politics.”

- 7Elke Zuern, “Why Protests Are Growing in South Africa,” Current History vol. 112 (May 2013): 175.

- 8Zuern, “Why Protests Are Growing in South Africa.”

- 9Hein Marais, South Africa, Limits to Change: The Political Economy of Transition (Zed Books, 2001).

- 10Kristin Henrard, “Post-apartheid South Africa: Transformation and Reconciliation,” World Affairs 166, no. 1 (2003): 42.

- 11In 2015, for instance, education received just under 20% of the 1.35-trillion-rand budget (a bit more than 107 billion US dollars); Budget Review 2015, Republic of South Africa, National Treasury website.

- 12Moeketsi Letseka, “South African Education Has Promises to Keep and Miles to Go,” Phi Delta Kappa no. 94 (March 1, 2013): 74–75.

- 13Simeon Maile, “The Absence of a Home Curriculum in Post-apartheid Education in South Africa,” International Journal of African Renaissance Studies 6, no. 2 (2011): 104.

- 14Gail Weldon, “A Comparative Study of the Construction of Memory and Identity in the Curriculum in Societies Emerging from Conflict: Rwanda and South Africa,” PhD dissertation, University of Pretoria, 2009, 150.

- 15Republic of South Africa Department of Higher Education and Training, “Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy, Republic of South Africa,” accessed July 26, 2015.

- 16Latoya Newman, “History That Embraces Africa,” The Mercury (South Africa), November 30, 2007, 12.

- 17Glynnis Underhill and Sibonile Khumalo, “No Justice for Burning Man,” Mail and Guardian, July 30, 2010, accessed June 4, 2015.

- 18Stephen Bevan, “The Tale of the Flaming Man Whose Picture Woke the World Up to South Africa’s Xenophobia,” Daily Mail online, June 9, 2008, accessed June 4, 2015.

Aftermath of the Ramaphosa Riots

Aftermath of the Ramaphosa Riots

A child pushes a trolley cart through burnt debris after violent xenophobic clashes at the Ramaphosa informal settlement on the outskirt of Johannesburg on May 21, 2008.

Many South Africans questioned why foreigners were the target of such violence after remarkable strides had been made to overcome decades of racial hatred. For some, the violence pointed to a need to address hatred and anti-migrant prejudice as well as the profound lingering inequality in South Africa. The persistent xenophobia also shed light on the need to continue the work of confronting the past, particularly the sensitive issues of the violence of the 1980s and the transition. Notably, many South Africans were pained by the violence, protested against it, and spoke about how the very people who were targeted in these attacks were from countries that had harboured South African refugees during the struggle against apartheid.

Migrant labor remains an integral part of South Africa’s economy, and studies have shown that migrants bring valuable skills into the country. The Consortium for Migrants and Refugees in South Africa, a collection of social service and activist organizations, argued in a public letter that the roots of the xenophobic violence were largely political:

Research conducted by the Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP) at Wits University has shown that the trigger for violence against foreign nationals or other ‘outsiders’ is primarily about competition for both formal and informal political power as well as economic power. Xenophobic violence in most cases has thus been the result of local leaders mobilising people to attack foreign nationals or other ‘outsiders’ as a means of strengthening their power in the local area. . . . Whilst it is widely acknowledged that immigration reform is needed to improve South Africa’s management of migration in order to better utilise migration as a development tool, we need to be extremely cautious in suggesting that illegal or irregular migration is the primary cause of xenophobic violence . . . . Tackling xenophobic violence and violence against other ‘outsiders’ is more about strengthening structures of governance and rule of law than tackling irregular migration. 1

- 1Duncan Breen, Consortium for Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA), “Causes of Xenophobic Violence,” July 21, 2009.

Demonstrations Against Xenophobia in Cape Town

Demonstrations Against Xenophobia in Cape Town

Groups of people hold banners and chant slogans during an anti-xenophobia demonstration in Khayelitsha region of Cape Town, South Africa on April 27, 2015 as a reaction to widespread anti-foreigner protests and violence.

The Shadow of Apartheid: Economics and Health

The 1994 elections that brought majority rule to South Africa and made Nelson Mandela president inspired great optimism in many people, both inside and outside the country. The new political system included impressive democratic structures, a new constitution, guaranteed minority representation, and strong legal protections of human rights. People enjoyed new freedoms of speech, movement, and assembly. With the majority black population finally in control of political institutions that had been used for decades to oppress and keep them in poverty, people hoped that new opportunities would open up for all people, leading to a redistribution of the country’s wealth.

View of Johannesburg

View of Johannesburg

A view of Johannesburg and its northern suburbs as seen from the top floor of the Carlton Centre, depicting the city’s modern infrastructure.

The economic legacies of apartheid, however, have proven difficult to overcome. In negotiations, as mentioned, the former government insisted on many protections for the white minority population, including the guarantee that white wealth would be protected. In 1994, shortly after Mandela’s election, the government passed the Restitution of Land Rights Act, a law that would allow individuals whose land was taken through discriminatory legislation dating back to 1913 to apply to have their land restored. But the bill faced strong opposition from both the right wing and the Inkatha Freedom Party, and in the end it had very little impact. When the parliament passed an amendment to the law in 2014 that sought to make it easier to reclaim stolen land, the Constitutional Court declared the amendment unconstitutional. The vast majority of South Africa’s most fertile farmland remains in the hands of white owners.

Improving the quality of housing for the black South Africans and correcting the gross inequalities in the education and health systems also proved to be daunting challenges. A significant portion of the population lived in temporary dwellings such as shacks or shantytowns, a problem that persists, as explored in the reading The Housing Clause in the South African Bill of Rights: The Continuing Struggle. The terrible conditions of schools and hospitals serving black communities meant that massive investments were needed, but the government was limited in how heavily it could tax the country’s wealthy (mostly white) population. The new government thus hoped that foreign investment could expand the economy and provide the income needed to fund social and economic improvements. These goals have been hard to meet, as investors were very slow to return, fearing instability after the transition. Many companies that had been willing to invest in South Africa when it was controlled by whites were initially unwilling to do so once black South Africans took power.

As a result, although the country has enjoyed steady economic growth and the income of the very poor has risen, gaps between rich and poor remain severe. Despite the promotion of a black middle class through initiatives such as the Black Economic Empowerment program, the majority of the country’s businesses are still owned by whites. Healthcare and education are more equitable than before, but millions of black South Africans still live in abject poverty. The freedom of movement that came with apartheid has meant that millions of people have migrated into urban areas, where the government’s program to build thousands of new homes has simply not been able to keep up with demand.

Although social programs have been implemented to improve the standard of living for South Africa’s poor, some argue that black laborers remain vulnerable to exploitation. This is especially true in the mining industry, which relies on a large number of migrant workers. According to 2015 reports, “[w]hites comprised 81 per cent of the highest income earners, Africans 10 per cent, Indians 5 per cent and Coloureds 4 per cent. Thus income inequality, always cited by critics of apartheid as one of the most important indicators of the effects of white supremacy, remains among the highest in the world in post-apartheid South Africa despite massive economic expansion.” Many mine workers continue to find employment miles from their families, living in squalid makeshift homes.

In addition, the World Bank recently reported that life expectancy at birth in South Africa is only slightly more than 60 years. 1 South Africa today is home to 5.7 million people who are H.I.V.-positive — more than any other nation, almost one in five adults. 2 According to another report, “In 2011, less than one in six households had adequate access to food, less than one in six individuals belonged to a medical aid scheme . . . and one in three adult South Africans still had no access to a formal financial institution.” 3

Tackling the AIDS crisis in South Africa has proven difficult, not just because of the number of cases and cost of treatment but also because of the attitudes of some leaders. Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor and president from 1999 to 2008, publicly disputed the scientific research into both the causes and treatment of the disease. During that time, South Africa faced an urgent and growing AIDS crisis; research by scientists at Harvard University now suggests that “the South African government would have prevented the premature deaths of 365,000 people earlier this decade if it had provided antiretroviral drugs to AIDS patients and widely administered drugs to help prevent pregnant women from infecting their babies.” 4 When Mbeki lost power, Barbara Hogan was brought in as health minister. She told reporters, “The era of denialism is over completely in South Africa.” 5

The Marikana Miners’ Strike and Massacre

The British-owned Lonmin platinum mine is located in Marikana, about 60 miles northwest of Johannesburg in the North West province. On August 10, 2012, 3,000 workers walked off the job, demanding more pay. The management called it an illegal strike. 6 The miners made approximately 5,000 rand per month in take-home pay (approximately $400 in 2018) and were demanding an increase of 2,500 rand (approximately $200) per month. Over the days that followed, the strike grew increasingly violent and came to include not just the striking parties but also policemen, security personnel from the mine, and an escalating rivalry between the National Union of Mineworkers and the more radical Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU). Ten people were killed in the early days of the strike, including two police officers and two security personnel.

On Thursday, August 16, the South African Police Service (SAPS) fired automatic weapons into the crowd of miners who were only a few feet away. Thirty-four people were killed, 78 people were injured, and 259 people were arrested. The SAPS claimed that they were under attack by miners carrying clubs, machetes, and spears. Some of the violence was documented by the media, including some police killings. Video footage showed that many of the strikers did not present a threat to the lives of the police officers. Some were standing too far away, others had no weapons, and still others were shot in the back.

News of what became known as the Marikana massacre quickly spread across South Africa and the world via traditional and social media. Many commentators made connections between the killings and the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, when police killed 69 people. Some have argued that the comparison is not in the details of the Marikana and Sharpeville events but in what they represent: an increasingly violent state and security forces using lethal force against people seeking dignified lives. In the case of Sharpeville, race played a critical role, with primarily white officers killing black South Africans. In the case of Marikana, the police officers were black. Writer Richard Stupart argues:

As events like Sharpeville made it impossible for our parents to claim ignorance about the violence of the apartheid state and the abominable inequality that made such repression necessary, so Marikana has made it impossible for us to claim to the next generation that we were unaware that the majority was being repressed. Predictably, there is outrage at appropriating a memory from our history and throwing it back at the current government. “The current government is vastly different to that of the old South Africa” runs the refrain. But there is a difference between “we are vastly different to the old South Africa” and “we have changed in all respects”. And it is in the respects that the state and nation have not changed that the comparisons to apartheid symbols like Sharpeville burn most incandescent. We are still a nation structured towards the economic exploitation of the majority. The state still uses violence to crush those who wish for a dignified life. 7

In the immediate wake of the massacre and this media attention, President Zuma formed the Marikana Commission of Inquiry and appointed judge Ian Farlam as its head. The commission issued its report in 2015. But little meaningful action has been taken to support the victims, their families, or the improvement of conditions for South African miners. Shortly after he came to office in 2018, President Ramaphosa told the parliament that the government had failed South Africa during the Marikana episode, saying that the tragedy “stands out as the darkest moment in the life of our young democracy.” 8

Looking Forward

South Africa entered 2018 in crisis. The president, Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma, stood accused of corruption and misconduct charges. Other members of the ANC governing party were known to be caught up in scandals, and the Constitutional Court ruled that the National Assembly had failed to hold President Zuma accountable. In February 2018, Zuma resigned, paving the way for Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa, the new head of the ANC, to become president. In his State of the Nation Address, Ramaphosa repeatedly invoked Nelson Mandela, calling on South Africans to continue the journey of transformation that Mandela began for them. Ramaphosa said:

We should honour Madiba [Mandela] by putting behind us the era of discord, disunity and disillusionment. We should put behind us the era of diminishing trust in public institutions and weakened confidence in leaders. We should put all the negativity that has dogged our country behind us because a new dawn is upon us. It is a new dawn that is inspired by our collective memory of Nelson Mandela and the changes that are unfolding. As we rid our minds of all negativity, we should reaffirm our belief that South Africa belongs to all who live in it. For though we are a diverse people, we are one nation. There are 57 million of us, each with different histories, languages, cultures, experiences, views and interests. Yet we are bound together by a common destiny. 9

Ramaphosa ended his speech with an appeal to memory and a call to action—a call for South Africans to make history together, to find opportunity for renewal and progress in the coming period of change. He concluded:

We have done it before and we will do it again — bonded by our common love for our country, resolute in our determination to overcome the challenges that lie ahead and convinced that by working together we will build the fair and just and decent society to which Nelson Mandela dedicated his life.

As I conclude, allow me to recall the words of the late great Bra Hugh Masekela [a legendary South African jazz musician].

In his song, ‘Thuma Mina’, he anticipated a day of renewal, of new beginnings.

He sang:

“I wanna be there when the people start to turn it around

When they triumph over poverty

I wanna be there when the people win the battle against AIDS

I wanna lend a hand

I wanna be there for the alcoholic

I wanna be there for the drug addict

I wanna be there for the victims of violence and abuse

I wanna lend a hand

Send me.” 10

Parliament responded with a standing ovation and by breaking into song.

In the days following the speech, journalists and commentators celebrated and critiqued it, and many pointed to the new feeling of hope in the air. They also addressed how close South Africa’s democracy came to the brink of disaster and turned a necessary spotlight on the essential roles that fundamental institutions—and the individuals within them—played in protecting liberal democracy, including a free press, an independent judiciary, and a strong civil society.

- 1The World Bank, “Life expectancy at birth total (years),” World Bank Open Data website, accessed June 2018.

- 2Celia W. Dugger, “Study Cites Toll of AIDS Policy in South Africa,” New York Times, November 25, 2016.

- 3“South African Economic Outlook,” Câmara de Comércio Luso-Sul Africana website, accessed May 23, 2018.

- 4Celia W. Dugger, “Study Cites Toll of AIDS Policy in South Africa,” New York Times, November 25, 2016.

- 5Dugger, “Study Cites Toll of AIDS Policy in South Africa.”

- 6It was formally an unprotected industrial action; see “Marikana Commission of Inquiry: Report on Matters of Public, National and International Concern Arising out of the Tragic Incidents at the Lonmin Mine in Marikana, in the North West Province” (South Africa Human Rights Commission), 55. For more information, see also “Marikana Massacre 16 August 2012,” South African History Online website; Greg Nicolson, “Marikana Report: Key Findings and Recommendations,” Daily Maverick, June 26, 2015; Nick Davies, “Marikana Massacre: The Untold Story of the Strike Leader Who Died for Workers’ Rights,” The Guardian, May 19, 2015.

- 7Richard Stupart, “Why Marikana Is Our Sharpeville,” African Scene, August 23, 2012.

- 8Jan Gerber, “Ramaphosa Promises 'Healing, Atonement' For Marikana,” Huffington Post, February 21, 2018.

- 9“Read Cyril Ramaphosa's first state of the nation address,” Times Live, February 16, 2018.

- 10“Read Cyril Ramaphosa's first state of the nation address,” Times Live.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “Introduction: Transition to Democracy,” last updated August 3, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.