Steve Biko Calls for Black Consciousness

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

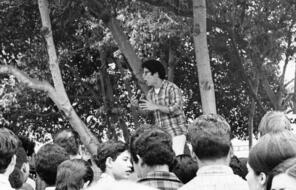

Politically, the decade from 1960 to 1970 was a period of deafening silence among black South Africans. The freedom movements of the 1950s had been banned and their leaders imprisoned. In the late 1960s, new young leaders arose, bringing a fresh concept for organizing called “black consciousness.” Foremost among these activists was Steve Biko. As a university student, Biko had been involved with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), a multiracial civil rights organization. Later, Biko began to rethink the role that racial identity should play in anti-apartheid activism. In 1968, he co-founded the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO). This new student organization, unlike NUSAS, was open to the three groups identified as black—native Africans, “coloureds,” and Asians—but it was not open to whites. The philosophical core of SASO was black consciousness: an assertive affirmation of black identity. Sympathetic whites were encouraged to form their own organizations to fight apartheid, but Biko and other leaders believed that it was important for black South Africans to take control of their own destinies, rather than relying on white support to bring their freedom. A core idea within the Black Consciousness Movement was the need for blacks to change their mentality and free their minds from the ideas of inferiority that apartheid had long encouraged.

In the selection below, from a speech Biko gave in 1971 at a nationwide multiracial student conference, he articulates his understanding of the connection between white racism and black consciousness. He saw the power that could come from organizing as blacks. Black Consciousness spread widely among youth and was a major spark igniting the 1976 Soweto uprising and leading to a resurgence in the national freedom movement. On June 16, 1976, in the segregated township of Soweto, thousands of black students walked out of their schools and marched defiantly through the streets, demanding an end to their second-class status in education and beyond. Students in other cities responded with similar demonstrations. Across the country, the paramilitary police came out in force, killing hundreds of teenagers and imprisoning thousands. The following year, in 1977, Steve Biko was imprisoned, tortured, and left to die. Yet thousands of others continued this struggle.

White Racism and Black Consciousness

We now come to the group that has longest enjoyed confidence from the black world—the [white] liberal establishment, including radical and leftist groups. The biggest mistake the black world ever made was to assume that whoever opposed apartheid was an ally. . . .

How many white people fighting for their version of a change in South Africa are really motivated by genuine concern and not by guilt? . . .

[A white person] possesses the natural passport to the exclusive pool of white privileges . . . . Yet at the back of his mind is a constant reminder that he is quite comfortable as things stand and therefore should not bother about change. . . .

I am not sneering at the liberals and their involvement. Neither am I suggesting that they are the most to blame for the black man’s plight. Rather I am illustrating the fundamental fact that total identification [by white liberals] with an oppressed group [blacks] in a system that forces one group to enjoy privilege and to live on the sweat of another, is impossible. . . .

The liberal must fight on his own and for himself. If they are true liberals they must realise that they themselves are oppressed, and that they must fight for their own freedom and not that of the nebulous “they” [blacks] with whom they can hardly claim identification. . . .

. . . [I]n South Africa political power has always rested with white society. Not only have the whites been guilty of being on the offensive but, by some skillful manoeuvres, they have managed to control the responses of the blacks to the provocation. Not only have they kicked the black but they have also told him how to react to the kick. . . . [H]e is now beginning to show signs that it is his right and duty to respond to the kick in the way he sees fit. . . .

It may be said that, on the broader political front, blacks in South Africa have not shown any overt signs of new thinking since the banning of their political parties [in 1960] . . .

The call for Black Consciousness is the most positive call to come from any group in the black world for a long time. It is more than just a reactionary rejection of whites by blacks. The quintessence of it is the realisation by the blacks that, in order to feature well in this game of power politics, they have to use the concept of group power and to build a strong foundation for this . . .

The philosophy of Black Consciousness, therefore, expresses group pride and the determination by the blacks to rise and attain the envisaged self. At the heart of this kind of thinking is the realisation by the blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed . . .

Slowly, they have cast aside the “morality argument” which prevented them from going it alone and are now learning that a lot of good can be derived from specific exclusion of whites from black institutions . . .

The growth of awareness among South African blacks has often been ascribed to influence from the American “Negro” movement. Yet it seems to me that this [awareness] is a sequel to the attainment of independence by so many African states within so short a time. . . . Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda’s . . . often quoted statement was, “[Malawi] is a black man’s country; any white man who does not like it must pack up and go.” . . .

Through the work of missionaries and the style of education adopted, the blacks were made to feel that the white man was some kind of god whose word could not be doubted . . . 1

To add to the white-oriented education received, the whole history of the black people is presented as a long lamentation of repeated defeats. Strangely enough, everybody has come to accept that the history of South Africa starts in 1652 [when the first whites arrived]. . . . We must seek to restore to the black people a sense of the great stress we used to lay on the value of human relationships; to highlight the fact that in the pre-van Riebeeck days [before whites arrived] we had a high regard for people, their property and life in general; to reduce the hold of technology over man and to reduce the materialistic element that is slowly creeping into the African character. In this age and day, one cannot but welcome the evolution of a positive outlook in the black world. 2

Connection Questions

-

In the first two paragraphs of the essay, Biko talks about the chasm between whites and blacks in South Africa. In his view, “the interests of blacks and whites in this country have . . . become . . . mutually exclusive.” What does he mean? Do you agree? How might Nelson Mandela have responded to black consciousness?

- Among the criticisms Biko raises against white liberals is that they operate out of guilt and, consequently, their objection to apartheid is weak. Do you agree? Do you believe that guilt offers only a weak rationale for opposing apartheid? Biko urges whites to rethink who they are in South Africa and to realize that they too are oppressed and should act as a white group to bring freedom to their country. Do you believe white South Africans were oppressed by apartheid? If so, in what way(s)?

- To clarify his argument about the role of whites in Africa, Biko approvingly quotes the founding president of Malawi, Dr. Banda. What does Banda ask whites to do?

- 1In his memoir, Nelson Mandela describes the moment in high school when the revered Xhosa poet warned the students that “‘For too long we have succumbed to the false gods of the white man. But we will emerge and cast off these foreign notions. . . . ’ I was galvanized.”

- 2Steve Biko, “White Racism and Black Consciousness,” in I Write What I Like: Selected Writings, ed. Aelred Stubbs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 63–72.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “Steve Biko Calls for Black Consciousness,” last updated July 31, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.